Calvin Cottar, at head of the table. Over his shoulder are the Cottar great white hunters. Photo by Chris Fletcher.

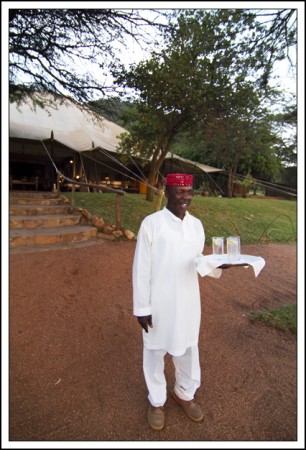

At dusk, old-fashioned paraffin and kerosene lamps are lit by the the Masai askaris and placed along the red pebble pathway, which gets raked by a young Masai every time a guest walks on it, leading from the individual tents to the dining pavilion, a large white canvas big top, like from a circus, held up with rough-cut poles and staked with rope. Dusty Oriental rugs on the floor and Victorian artifacts—a brass telescope, safari hats hanging over the backs of canvas chairs, a wind-up gramophone record player—are spread about.

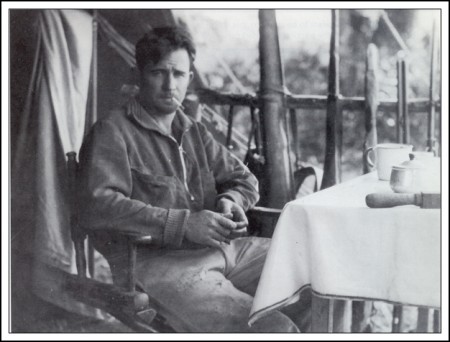

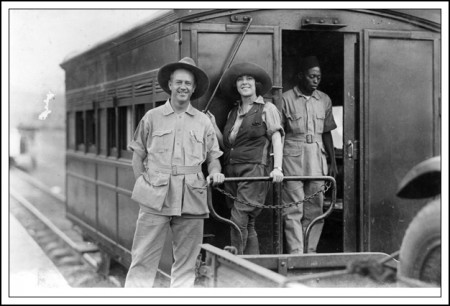

There are two linen-covered dining room tables on opposite sides of the tent separated by a little sitting area styled like a colonial corner of the Lord Delamere Bar at the Norfolk Hotel. Most of the guests eat communally at the larger dining table lit by candles and decorated with jars of fragrant wild sage called leleshwa. We sit at a smaller table across the room next to an Edwardian bookcase with antique books, long out of print, like Hunting, Settling and Remembering by the big-game hunter Philip Percival. To the right of that are four framed black-and-white photos of Cottars going back almost a hundred years: the patriarch, Charles; his two sons, Bud and Mike; and Glen, Calvin’s father.

When we dine at this table, Calvin sits with the three generations of Cottar men looking over his shoulder. No doubt he feels them looking at him all the time. There has been a Cottar running a safari camp since 1919 and it goes unsaid that Calvin feels the weight of keeping that going.

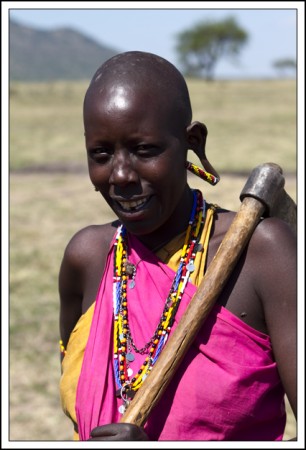

After dinner we retire to the comfort of the canvas chairs around the campfire, now burning low and steady, fed every once in awhile with a branch or two of hard wood by the tall Masai crouched nearby in the darkness beneath an umbrella acacia. Now it is time for the whisky.

At one point Calvin gets up and his chair is taken by a dark-haired woman who happily accepts our offer of a glass of smoky Lagavulin. She and her husband, who sits slouched in a chair on the opposite side of the fire, have just gotten back from a night walk looking for leopards. They’d seen three, nearby, and she is still feeling the adrenalin rush of stalking leopards at night, by foot, her euphoria evident in the rush of words as she tells us all about it.

She knocks back the whisky quickly and Hardy pours her another while gently flirting with her. She’s a doctor, from San Francisco, specializing in tropical diseases, a bit of an expert it seems. Her husband, who seems to be sulking and has hardly said a word while sipping a diet soda, is also a doctor, though it seems obvious she has the more prestigious job.

There is some strange dynamic going on between the two of them; it’s obvious to all of us. She’s talkative, vivacious, drunk on Africa, happy to be sitting around a campfire surrounded by four strange men, sharing their whisky and their stories. He’s morose, slumped, silent, purposefully sitting alone on the dark side of the fire.

Perhaps they’ve quarreled earlier in the evening. Or maybe he just doesn’t like it that she is so comfortable here. Did something happen while they were out looking for leopards? It’s impossible to tell. But we’re all aware that something is up and, perhaps a touch meanly, we play to it. We laugh with her, ask her for more stories, refill her glass. At one point, Hardy, who has brought a box of Cuban cigars along on the trip, asks her if she’d like one. Her dark eyes get wide. Which is when her husband stands up and goes over to her. Standing behind her canvas chair he says, “We’re getting up awfully early tomorrow to go out with Phillip. We probably should go to bed.”

You can tell from her expression that’s the last thing she wants to do. Without answering him she swallows the last of her peaty whisky, licks her lips, and stands up. “Gentlemen, it was a great pleasure to meet you and share your whisky,” she says, shaking each of our hands. “Have a pleasant evening.”

And then they walk off into the night, her a little tipsy, striding ahead of her husband, being led by a Masai askari carrying a kerosene lantern.

Recent Comments