In his book White Hunters: The Golden Age of African Safaris, author and big-game hunter Brian Herne notes that, up until WWII, it wasn’t at all unusual for a safari to last three, five, or even nine months. It all depended on how serious you were about getting a proper trophy of the Big Five: elephant, rhino, buffalo, lion, and leopard. The thing is, you weren’t going after the animals willy-nilly; you went after elephant depending on where your guide thought you might have the best chance, and when you bagged one, the entire safari troupe–which could easily be made up of 20 or 30 men, including cooks, porters, gunbearers, trackers, and even a taxidermist—moved on to the next site, miles away, in search of lion or buffalo or whatever.

This is all made quite clear in Hemingway’s Green Hills of Africa (Hem’s was a relatively short two-month safari) when he writes about running out of time hunting in a certain part of the country and the need to make a choice before the rains come whether to stay for one or two more days and get his bull or move on and hunt for something else.

“I knew there were only two days more to hunt before we must leave. M’Cola knew it too, and we were hunting together now, with no feeling of superiority on either side any more, only a shortness of time…”

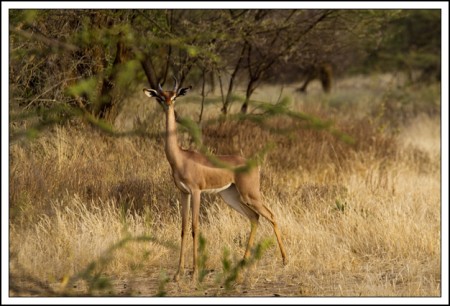

Big game hunting has been banned in Kenya for over 30 years, but even now everyone comes to Africa wanting to shoot the Big Five, at least with their camera.

But a few years ago, someone suggested going on safari to shoot the “Small Five”—aardvark, serval, mongoose, hyrax, and the African porcupine. I have to say, I’ve never seen any of the Small Five in the wilderness—until last night.

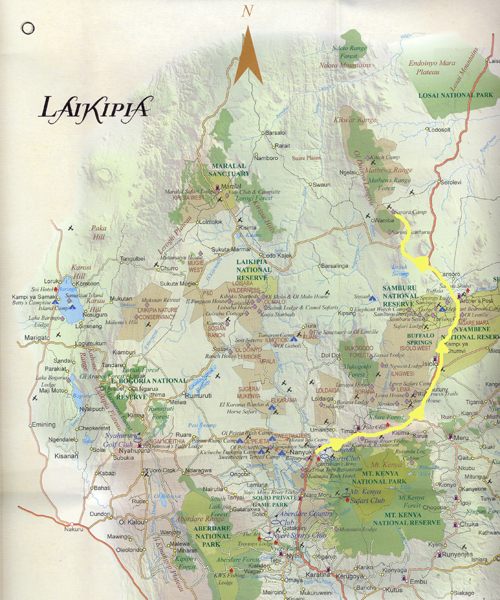

We were just bumbling along through the bush in the darkness, going very slow both because it was difficult to see more than ten feet down the road because of the head-high commiphora thickets and because we weren’t at all sure where we were going. So we were all doing that thing you do at night when you’re a little bit lost on an unfamiliar road—leaning forwards and staring very intensely at the darkness directly in front of you. Suddenly there were several large black lumps moving across the road ten or twenty feet in front of us.

“Jesus!” Fletch said, startled. “What the hell is that?”

Calvin immediately stopped the Land Cruiser. And we all stared. At a family of African porcupines, a couple of them at least a couple of feet long, rambling across the rutted road.

“There aren’t porcupines in Africa, are there?” Fletch asked.

Well, yes, there are. You just never see them because, of course, they’re nocturnal. And who is out in the bush at night? Just people like us who are lost and hours behind schedule.

Crested porcupine, according to my wildlife guide, are the largest rodents in East Africa. “Their mainly nocturnal habits make them rare to see.” Well, good for us then.

The guide also said the belief that the quills can be shot by the animal is a myth. Evidently what they do, if threatened, is stamp their feet, click their teeth, and hiss at you (hmmm…sounds like an editor I know). If that doesn’t work, “the porcupine runs backward until it rams its attacker. The reverse charge is most effective because the hindquarters are the most heavily armed and the quills are directed to the rear.”

Brilliant.

So now I’ve bagged one of the Small Five. Next up (I hope): maybe an aardvark?

Recent Comments