Leaning against the seawall beside the old White Star Line pier, a white fedora shading his sunburnt cheeks, is Michael Martin. Dr. Michael Martin (as of June), he tells me. We walk the pier together. Do you know of Father Frank Browne, says he. I do not. Ah, well. A Jesuit priest from Cork.

I walk on, head down, scuffing at the worn planks, knowing there’s more to the story but giving Michael Martin space in the breeze to fill it in as he wants.

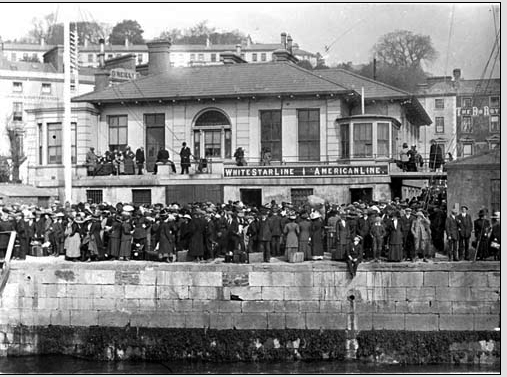

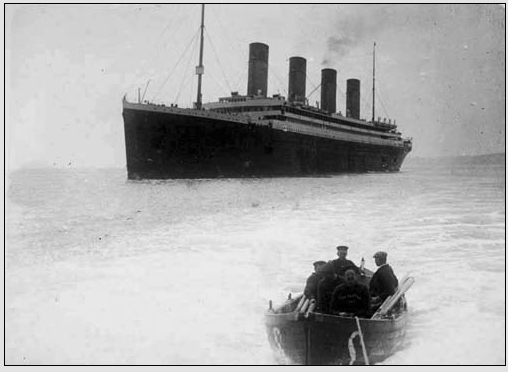

Steerage passengers waiting to embark on tenders for the Titanic at White Star Wharf, Queenstown (Cobh). Photos by Father Frank Browne.

Curious story, says Michael Martin, stopping to wave at a Cobh fisherman walking up the beach with nets over his shoulder. His uncle was the Bishop of Cloyne. Rather fond of his young nephew. Encouraged his interest in photography by sending him all sorts of fancy cameras and such. Not the normal thing for a young noviate. Then one day in April 1912 he gets a most unusual present from the Bishop: a first-class ticket for the first legs of the maiden voyage of the Titanic, sailing from Southampton to Cherbourg and then on to what was then Queenstown and is now called Cobh. Right where we’re standing.

Michael Martin interrupts his tale to chat with the fisherman. What are you catching then? Not much of anything today. No matter. Lovely weather, after all. Isn’t it? But they say rain in the afternoon. Oh, well, that’s just to keep us from getting sunburnt, isn’t it.

We walk on. Michael Martin seems to have forgotten his story. I remind him: So this Father…?

Oh, yes. Father Browne. Well, he gets on board the Titanic and sails off to Cherbourg taking dozens of photographs—Captain Smith, the Marconi room, kids playing on the decks. That sort of thing. And at dinner, he’s seated at the table of an American millionaire who’s quite taken by the young Jesuit and offers to pay his way in first-class for the rest of the voyage to New York. Imagine that?

Michael Martin moves off down the pier. Starts talking about two red tugboats in the harbor. Damn this man. Why can’t he just finish his story? Making me beg for it.

Did he go then?

Who?

Father Browne, of course!

Oh, Father Browne. Michael Martin takes off his fedora, studies the blue sky as if the answers might be printed in the clouds, returns the hat to his head. Well, here’s the thing, he says in a whisper, drawing close to me. He had to get permission from his Jesuit Superior, didn’t he? So he wired him and when the ship reached Queenstown there was a cable waiting for Father Browne.

What did it say for chrissakes?

Ah. Well. There were only four words in the cable.

And they were?

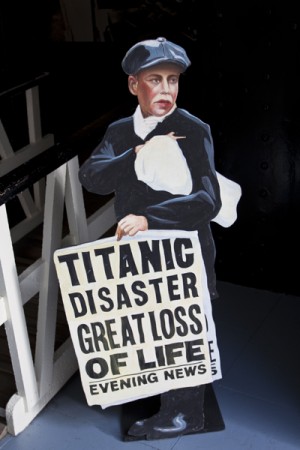

GET OFF THAT SHIP! Michael Martin laughs. Funniest thing he’s ever heard. So funny he repeats it: GET OFF THAT SHIP! A bit tetchy, wouldn’t you say? But orders are orders. So Father Browne gets off the Titanic in Cobh. Takes a few more photos of the ship as his tender transfers him to the pier where we’re now standing. Last man off. Ship sails off. Never to be seen by human eyes again. And Father Frank Browne has the only photos taken of the old girl sailing at sea. And they’re published on the front pages of newspapers all over the world. Imagine. And it’s only his cranky ol’ Jesuit superior that saved his life. Telling him to get off that ship. Off indeed. Off he got.

But there’s one final part of the story, Michael Martin says. Father Browne lived the good life of a Jesuit priest until dying in 1960. And his great collection of negatives lay forgotten for 25 years. At which point another Jesuit priest comes across a large metal trunk with thousands of negatives. Including those of the Titanic. And he passes them on to the features editor of the London Sunday Times who dubs them the photographic equivalent to the discovery of the Dead Sea Scrolls. Imagine that. Lost for 25 years.

Michael Martin takes off his fedora once again, scratches his sunburnt pate, shakes his head, replaces the hat and ambles on. Leaving me along on the pier to think of Father Frank Browne and the Titanic.

Recent Comments