There are two rainy seasons in Kenya. The first, which generally runs between March and May, is called the “long rains.” The second, between November and December, is the “short rains” or “little rains.”

Last year there were no long or short rains, and the year before that, very little. So this year when the rains came in January and continued pretty much straight through May, people didn’t know what to call them.

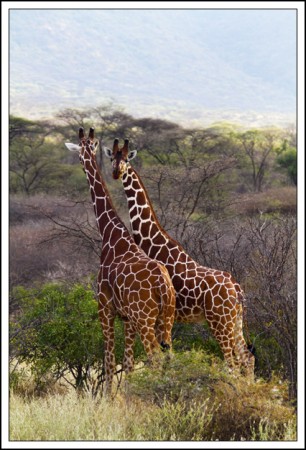

Water is life everywhere. It just seems more acutely real in Kenya. If the rain does not fall when it is supposed to, the cattle die, the wildlife dies, and, if the maize fails, the people die. All of this happened in such grand proportions that in January of last year, the Kenyan government declared a national emergency over the extended drought.

And then in November the short rains came and just kept on coming. Which, of course, can cause as many problems as no rain. This summer, there was so much maize harvested that Kenyan farmers couldn’t sell it. “Where do you want us to put it?” said the usual buyers whose silos were already full. So it rotted. And the farmers went hungry. Again.

It’s a conundrum.

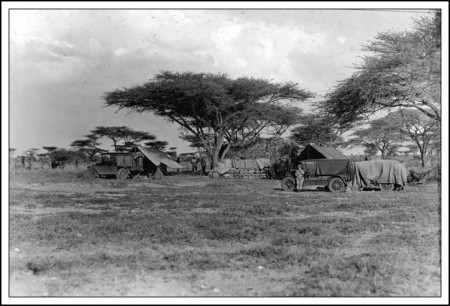

Up here in the Northern Frontier District the major river is the Guaso Nyiro (which flooded its banks and caused major damage in the spring). And then there are the luggas, or sand rivers.

During the dry season (which we are towards the end of, assuming the little rains come next month), the Samburu and other pastoralists in this area like the Rendille, herd their cows and goats and camels from one patch of meager grazing to another, watering them in the same sand rivers that have been used for hundreds of years by these people.

In the sand river, they dig a hole just deep enough until they find water and then they take a bucket or an old vegetable oil tin and fill it with water for their stock. Of course, as the dry season goes on, the water is harder to come by and the hole gets deeper and deeper. Eventually it might be 15 or 20 feet deep, necessitating a chain of three or four lmurran passing the bucket from hand to hand, all while they sing a lilting chant that reverberates all along the sand river where four or five other groups of warrior herdsmen are doing the same thing. For this reason, they are called the singing wells.

That’s the scene we came across quite accidentally this morning. We were out and about looking for Grevy’s zebra (which I still haven’t seen) when we heard this strange, hypnotic music wafting across the sand river we were crossing. We went to check it out and came across several groups of herdsmen watering their cows while singing. Magical.

Recent Comments