You are currently browsing the archive for the Scotland category.

The roads on Islay are narrow and lined with bracken and wildflowers: delicate foxglove, creamy astilbe, lacy Queen Ann’s lace, Monet-colored lilies, and arching penstemon, as well as wild gooseberries, goldenrod, daisies, purple thistle, wild fuscias, and the odd lilac. A riotous border of color enclosing fields of lime green grazing pastures. This is the landscape Van Gogh would have painted had he been Scottish.

My favorite Western Isles wildflower is the ragged robin, not so much because of its looks (which remind me of a droopy pink daisy) but because they cheerfully bloom in absolutely the worst conditions imaginable—damp and peaty meadows. This silly flower just loves poor soil. In fact, the best way to kill it is to fertilize it. Which means that while it used to be found all over the UK, it’s pretty much died out, mostly because of all the fertilizers used in the fields. But there are still enough damp, forgotten fields on Islay where it blooms from May to September to put on quite a spectacular show.

The other thing I like about it is a story, likely to be apocryphal, that Charles told me. He said that a hundred or more years ago, young Scottish lassies use to grow ragged robin in summer, naming each of their plants after a boy in the village. The first plant to bloom would be the boy the girl was going to end up marrying. Sort of a Scottish version of “he loves me, he loves me not.”

Although almost everyone who comes to Islay does so for the whisky (myself included) it really has some spectacular flora and fauna. In fact, Islay has some of the most amazing birdlife in all of the UK (with over 180 species, it has the richest bird life in the Hebrides). There are snipes and lapwings, choughs, hen harriers, golden eagles, countless species of geese, and, of course, the ever secretive corncrake which, should you be lucky enough to spot one, looks a bit like a small pheasant.

Yesterday as I was walking through some heavy grass to take a picture of the ragged robins, I heard the distinctive rasp of corncrakes and followed the call to a clump of nettles. Two of the little guys hung around just long enough for me to snap a picture before disappearing into the thick grass.

Like ragged robins, they tend to depart towards the end of August, first of September. So for me to spot both of these rarities on the same day right next to each other was golden.

And fleeting.

I’d always sort of imagined whisky distilleries as being bustling places with lots of red-faced Scots scurrying about doing this and that. But actually it doesn’t take many people to make whisky. A handful, really. And if you visit a Scottish distillery this time of year, you’re likely to find it mostly deserted. Or closed (many traditionally do maintenance in August or just shutter the doors completely).

That was pretty much the situation at Bruichladdich (brook-laddie) when Charles and I showed up this morning around 10. The gates were open but we didn’t see a single soul on the premises. Eventually we ended up in the little shop that serves as a visitor center of sorts where a middle-aged woman reading a book seemed surprised to see us.

She said the only one around at the moment, other than herself, was one of the four partners, Andrew Gray, and he’d be happy to show us around if she could only find him. So while she’s out looking for Andrew, let me tell you a little bit about this unique distillery.

First of all, Bruichladdich is a bit of a whisky phoenix. Like a lot of Scottish distilleries, Bruichladdich had its ups and downs over the years (there used to be 25 distilleries on Islay; now there are 7).

Bruichladdich itself closed for a spell in the late ‘80s before being acquired by four separate corporate owners (including Jim Beam and Fortune Brands) from 1992 to 1994. But nobody really seemed to know what to do with the company and in 1994, the distillery was pretty much closed down for good, devastating the town on the west coast of Islay.

Then four friends—Mark Reynier, Simon Coughlin, Jim McEwan, and Andrew Gray—got together and purchased the closed distillery in December 2000. After months of restoration work, Bruichladdich officially reopened on May 29, 2001 before a crowd of 3,400 ecstatic islanders (a good chunk of the population). They now have 47 employees, all from Islay, and in just a few short years have won a number of prestigious awards, including Distillery of the Year three times. Kind of a nice story, don’t you think, particularly in an age when most of the Scottish distilleries are now owned by huge international conglomerates like Diageo (in fact, the company, whose philosophy is to be “fiercely independent, non-comformist, and innovative—the enfant terrible of the industry” refuses to join the Scotch Whisky Association because, they say, “We feel our independent status and freedom of expression would be compromised” by the council whose board includes three members from Pernod and three from Diageo).

Anyway, Andrew was eventually rounded up and for the next couple of hours, we sat around with him loosely discussing Islay whiskies in general and Bruichladdich in particular.

“The characteristic of the western islands is they get a lot of rain—as much as 160 inches a year. So the ground is very wet and there are lots of bogs. Peat is a primary heating source and the whisky coming from Islay have a real smoky, peat flavor that people either love or hate—there’s no middle ground with this whisky. Plus all the distilleries are situated by the sea. The casks are all maturing in a briny, salty atmosphere. There’s often salt caked on the outside of the casks. It seasons the casks and gives them a different flavor.”

That said, Andrew said that Bruichladdich, which contains about 5 parts per million of peat, isn’t nearly as smoky tasting as whiskies like Lagavulin and Laphroaig which contain between 35 and 45 parts per million.

Then Andrew immediately contradicted himself by pouring us a dram of a new Islay single malt they’re distilling called Octomore. Now I love Laphroaig but I have to say I could hardly swallow Octomore. Andrew chuckled at my reaction. “That’ll put hair on your chest, eh,” he said. To be sure. The whisky, which Andrew calls “for serious peat freaks,” has a mind-boggling 131 parts of peat per million.

With the subtlety of a sledgehammer, it’s definitely not for everyone—including me. But I love the idea that these “fiercely independent, non-conformist” whisky makers, who brought this distillery back from extinction, have the balls to make it. It’s certainly not something you can imagine Pernod or Diageo ever doing.

Charles and I were both downstairs early this morning, anxious to tuck into the Port Charlotte Hotel’s Full Scottish Breakfast, or FSB as Charles call it. There are small variances from inn to inn, of course, but basically a FSB includes a starter of porridge and perhaps canned grapefruit slices followed by a heaping plate of rashers (bacon), black pudding (blood sausage), sausages, eggs, grilled tomato, mushrooms, baked beans, and Tattie scones (potato scones). The Port Charlotte also offers plate-sized kippers or “Arbroath smokies” (smoked haddock) if you’re not a meat eater. Along with juice and coffee or tea, of course.

As Charles said when our meal arrived, “A pretty standard FSB.”

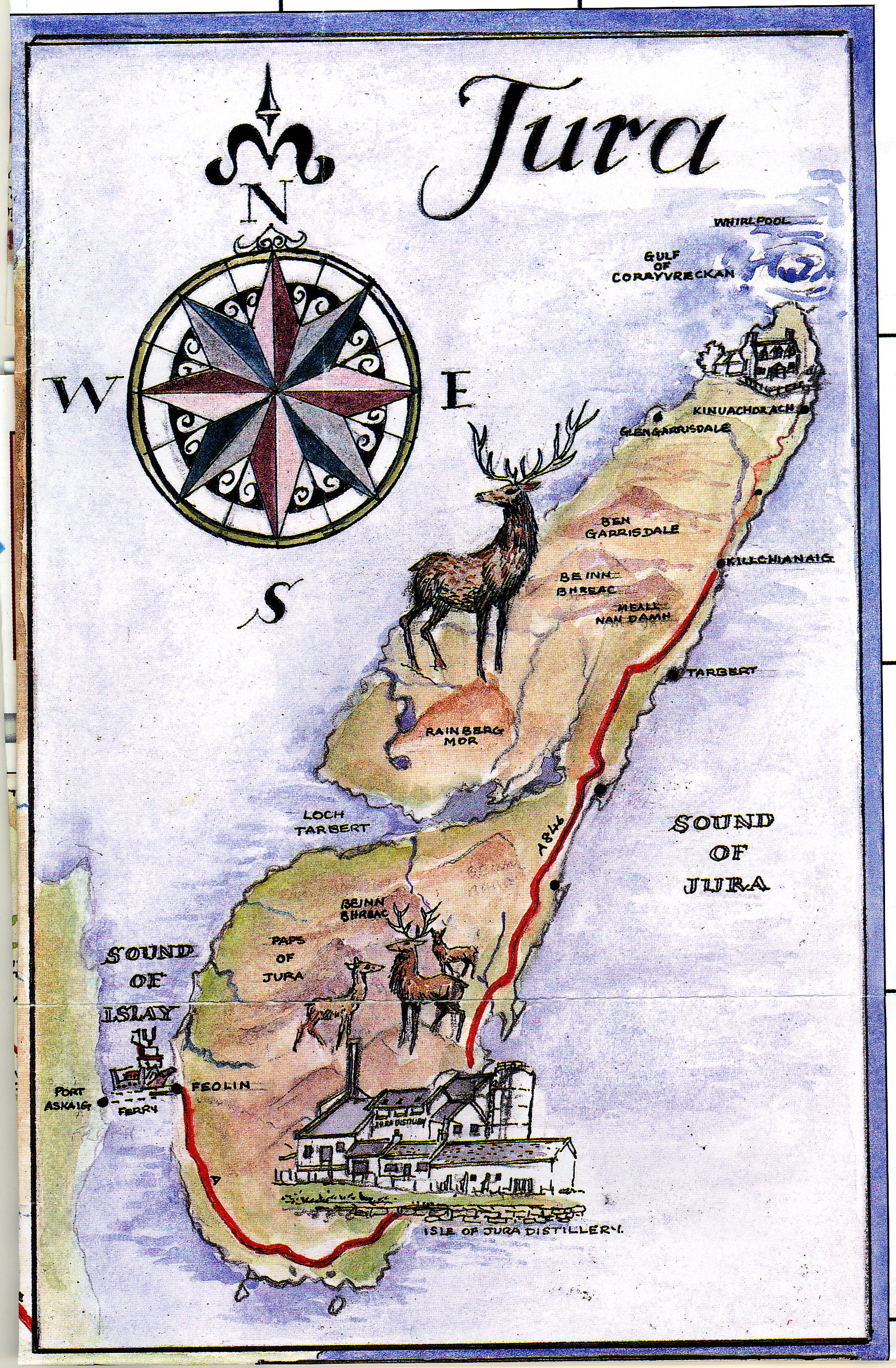

Over breakfast we talk about our upcoming day which includes a visit to the Bruichladdich distillery and then a short ferry ride over to the island of Jura. When I suggest we take a look at the map to plot our route, Charles waves me off.

“There’s only one road,” he says indignantly. “We can hardly get lost even if we’d like to.”

We’ll see.

As we’re driving through the Scottish countryside, I ask Charles if he’s married. “Aye,” he says, “to a remarkable woman.” They live in a little village called Balquhidder (from the Gaelic “Baile-chuil-tir” which means “the distant farm”) a place so remote, he says, that no one can ever find it. “Which is fine with me.”

There’s not much to do in Balquhidder, Charles says, “So we need to entertain ourselves.” He’s in a singing group but his wife can’t carry a tune, he says. So she decided, at the age of 43, to take up the accordion, mostly because if you’re going to learn an instrument in Balquhidder it has to be the accordion since “all we’ve got is the one accordion teacher.”

Fair enough.

The only problem, Charles says, is that the other two students taking accordion lessons with his wife were both under 12. Still, she’d not be dissuaded. After a year or so of accordion lessons, the town had a ceilidh in which Charles was going to sing and his wife was going to play the accordion. Obviously, he said, he was more nervous for her than for himself.

And how’d she do? I asked.

Charles got a big lovely grin on his face. “It was brilliant,” he said.

Later we stopped at the Crannog seafood restaurant in Fort William for lunch, sitting loch-side next to the town pier, relaxing in the sun. I was tempted to get the cullen skink, just to see how it matched up to Topi’s, but decided I didn’t want to smudge my memories one way or the other, so instead I had the house hot and cold smoked salmon and rainbow trout in lemon butter along with a Kelpie Seaweed Ale.

Seaweed ale? It sounds more exotic than it is. The Scots have made beer from local malted barley grown in fields fertilized with seaweed harvested on the Argyll coast for over two hundred years. They say the seaweed (called bladder rack) gives the beer a particular “aroma of the sea” but I didn’t get that. The Kelpie (which is the Gaelic term for the mythical creatures who live in the lochs of Scotland, the most famous being the Loch Ness Monster of course) was dark brown and a little chocolaty with maybe a sniff of smoke in the creamy head. But I didn’t get any seaweed.

Still, it was good enough to order a second. I sipped it out on the deck, wondering how long it might take me to learn how to play the accordion.

Recent Comments