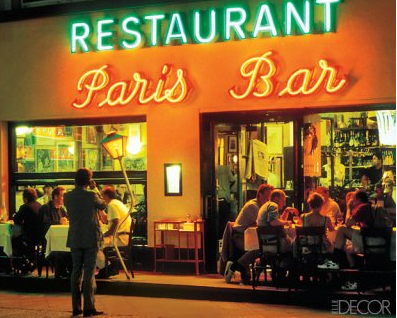

I have never met anyone, Berliner or not, who did not wrinkle their nose when speaking of one of Berlin’s most famous dining institutions, the Paris Bar. The food is mediocre, the décor dusty, and the waiters rude even by French standards (the Germans have a word for rude Berliners; they are called Berliner Schnauzers, like the dogs). Yet sooner or later, everyone in Berlin ends up here—directors, German movie stars, writers. I myself have dined there three times in the past week, though only once by choice.

I have never met anyone, Berliner or not, who did not wrinkle their nose when speaking of one of Berlin’s most famous dining institutions, the Paris Bar. The food is mediocre, the décor dusty, and the waiters rude even by French standards (the Germans have a word for rude Berliners; they are called Berliner Schnauzers, like the dogs). Yet sooner or later, everyone in Berlin ends up here—directors, German movie stars, writers. I myself have dined there three times in the past week, though only once by choice.

There was the young Berlin director who said, “It’s a horrible place but we should at least put in an appearance,” and the photographer from Cologne, Hanne, who first told me everything she despises about the place and then insisted we take a $30 cab ride across town at one in the morning for an espresso so I could see for myself why it was not worth coming to. On that evening when I gave our sultry waiter my VISA card, he shook his head violently, just like in the commercials, and said, “Nay, nay—only American Express.”

And so, of course, this is where I end up on my last evening in Berlin. The Paris Bar. Being told I cannot sit at one table because it is reserved, though there is no sign on it and, while I dine, no one ever sits there, and being completely ignored by my waiter who stands just outside the front door morosely watching the traffic go by and smoking Gauloises. When he finally deems to come over, he gives me a German “pffff” when I order the lamb cutlets, as if he cannot believe I have interrupted his philosophical musings on the Blvd. Kantstrasse for such a plebian order.

The German mother and her twenty-something daughter dining next to me get the same reaction when they tell the waiter they want to split a dessert, and they both shake their heads in disgust at the waiter’s surliness before putting their hands over their mouths and giggling. For this is the point about the Paris Bar: It is such a rude establishment and so counter to the general good manners of Germans that it is, in and of itself, an entertainment in the city. Like going to a show.

To further annoy my waiter, I order an espresso after my meal and just as he delivers it, the Polezei pull up across the street, followed by a tow truck. Two policemen, along with the tow truck driver, huddle around the old Trabi that I have been enviously eyeing for weeks. It’s the same one whose owner told me I couldn’t drive it because it didn’t have an engine.

The tow truck driver quickly hooks up the little cardboard car and off it goes. One less sad old East German Trabi on the streets of der neue Berlin. As the tow truck passes by the restaurant, the Trabi dangling behind like a too-small fish, the woman at the table next to me points to a hand-painted sign hanging from the ceiling of the Paris Bar: Stand Still and Rot.

We smile at each other. In Berlin, this is more than just a saying. It is the zeitgeist of a city always changing.

Recent Comments