All day it has been threatening rain and now, as if on purpose, the sky has almost cleared for the Berlin Open Air Classic Concert situated dramatically between two churches—the French Cathedral and the German Cathedral—in the Gendarmenmarkt. While a marble statue of the poet Schiller looks sternly down on the audience , dressed in their finest Heidelberg green vests and Munichen skirts, one soprano after the other, all in gorgeous low-cut gowns displaying an abundance of German cleavage, are paraded out on to the steps of the Concert Hall to sing American classics—Gershwin, Bernstein, Ellington—as well as Mozart. (One way or the other they have to get the Mozart in.)

A baritone in red and black bow tie comes out and sings something that seems terribly funny to the boys in the chorus who poke each other in the ribs and laugh to the sky before singing a resounding chorus to many bravos and great applause signaling the intermission.

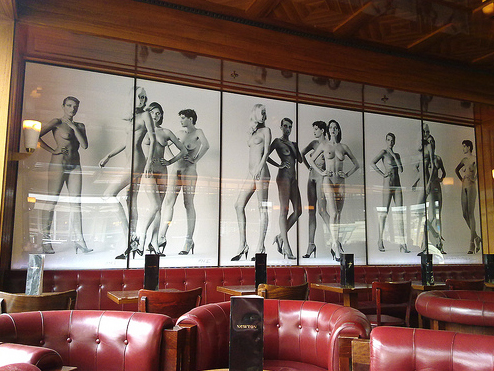

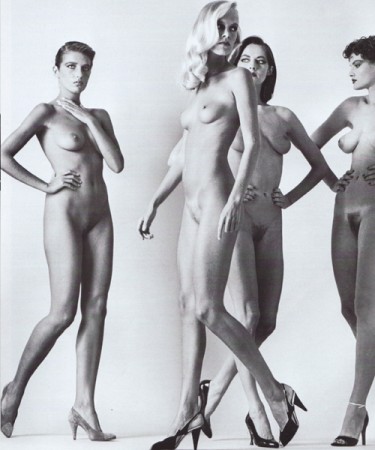

I’ve had enough. I skip the second part of the concert and wander across the street to Newton, a classy bar named for the legendary Berlin fashion photographer Helmut Newton. The counter is green marble, the leather armchairs are red, and on the walls are life-sized black-and-white nude amazons from Newton’s famous “Big Nudes” series.

I order a Sekt and sit at the bar. Sitting on my left are a couple of guys making out. On my right are two attractive young women. The one closest to me turns and asks if I have a lighter. I tell her I don’t smoke. “Good for you,” she says. The bartender lights her cigarette and then she turns back towards me and asks if I would like to buy her and her girlfriend a glass of Sekt. “We like it here,” she says, “but the drinks are too expensive.”

I buy them both a glass of Sekt. The one with the cigarette is named Kerstin and her friend’s name is Eva. They ask me what I think of the photos of the amazons. I tell them I like them. “Ya,” says Kerstin, “except they look more like mannequins than real people.”

I tell her that maybe that was Newton’s point. That when we see models wearing clothes, we don’t really see the models. They’re just walking mannequins.

“Maybe that’s so,” says Kerstin. The two women finish their drinks and stand up, putting on their coats. I ask them why they are leaving so early. “We are sharing a babysitter and we told her we’d be home by eleven,” says Kerstin. And then they leave, to go look for a taxi, just as the rain begins. I order another glass of Sekt and wait out the storm.

Recent Comments