The plan was to get an early start and take Unplugged’s tender to Cayo Levisa, a tiny island in the Los Colorados archipelago on the northwest end of Cuba, and catch the morning ferry to Palma Rubia where we’d hire taxis to take us up to the famed Valle de Viñales where they grow most of the tobacco for Cuban cigars in dusty red earth.

We’d done our due diligence the afternoon before. We knew the ferry schedule, knew how much it would cost, knew how to go about getting several taxis for the half-hour drive to Viñales, the old Colonial town in the middle of Pinar del Río. The only thing we didn’t know about was Eliaz.

Eliaz was the baby-faced Cuban immigration officer who met us on the dock at Cayo Levisa and promptly let us know that it would not be possible to take the ferry to Palma Rubia.

“Por qué?”

Because we did not have permission to take the ferry.

Yes, but we had permission to sail to Cayo Levisa and we have permission to visit Viñales.

Perhaps. But we did not have permission to take the ferry to Palma Rubia and if you do not have permission to take the ferry, then you cannot go to Viñales. Simple as that.

If this were Mexico, we would have slipped Eliaz $20 or $40 and been done with it. But it is a tricky thing to offer a mordida in Cuba. Particularly to a young man wearing a loose-fitting green army uniform who looks like he has never shaved.

This is when it is good to have a lawyer on board. Which we did. Ian. The only problem was that Ian was British and spoke little Spanish beyond “Otra cerveza, por favor.” Still, Ian and the boys, with Fletch translating, gave it their best shot. Perhaps if our captain came ashore, they suggested, and brought the proper paperwork?

Eliaz shrugged. “You have permission to go on land from Cayo Levisa?” he asked.

“Claro,” Fletcher lied.

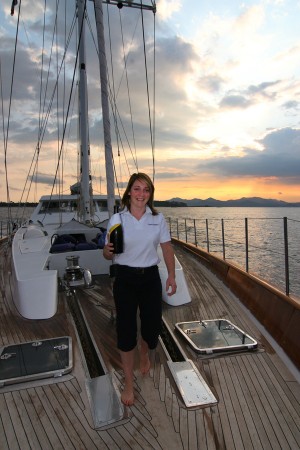

So Hardy radioed Craig and the Unplugged’s captain returned with several pieces of official documents as well as Malin and the girls. The documents were useless. But Malin, who is Swedish by birth and, like most Scandinavians, seems to speak about a dozen languages, proved invaluable. She smiled. She flirted. And she spoke wonderful Spanish.

Soon Malin the Magnificent, Ian the Barrister, and Captain Craig were following the little Cuban bureaucrat, Eliaz, down the dock to an office inside the Cayo Levisa resort where calls were made to the Cuban authorities at Marina Hemingway.

While this was going on, the rest of us hung out along the white sandy beaches, which wasn’t the worst place to be, waiting and waiting and waiting for something to happen. Every ten or fifteen minutes, Malin or Ian would come out of the office and give us an update. A call had been made. Papers were being searched. The proper people were being contacted.

Meanwhile, the morning ferry had come and gone.

After an hour or so, news came from Havana: With a small payment made, we could go to Viñales. More negotiations proceeded as we hired a fishing boat to take us over to Palma Rubia. Half an hour later, we were crossing the channel. Someone on the fishing boat even offered to make us mid-morning mojitos. Lovely. We accepted. Now we just have to hope that there will actually be taxis in Palma Rubia to take us up to Viñales.

Recent Comments