Unbeknownst to me, Ketsara evidently decided last night that we were not going to the opium museum in Chiang Saen today.

“But why, Khun Ketsara?”

“Why you want to go?”

“I think it might be interesting.”

Ketsara doesn’t say anything. I think she’s protecting me. I think she’s worried about the effect certain dark things on this trip might have on me. It’s true I’ve been a little moody lately. But what does she think is going to happen at the opium museum? Certainly they’re not giving away free samples, are they?

In the end, she relents. “Quick stop,” she says. “Fifteen minutes.”

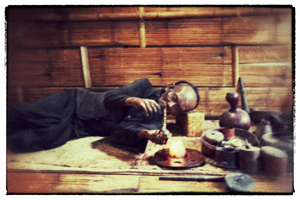

The museum is dark—literally and figuratively. In small rooms they house hundreds of opium pipes, many charred and thick with old opium paste, porcelain jars for storing the drug, and the elaborate scales used to measure the opium. But what I find particularly spooky are the dioramas of opium dens, some so realistic looking that it takes you a moment to realize that the drugged out Chinaman lying on his side lighting an opium pipe isn’t real…is he?

I walk briskly through the museum. Ketsara was right, I really don’t need to see this. Or at least, I don’t need to linger. After about ten minutes of wandering around, I am dying for some fresh air. And light.

Recent Comments