Osa Martin was smiling here after Martin purchased some camels for their safari, but the camels got the last laugh.

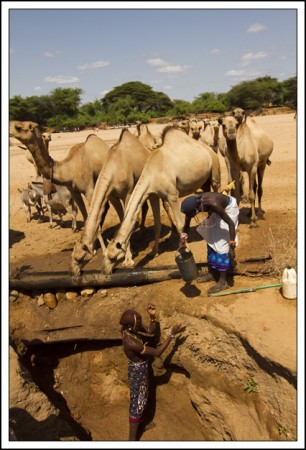

Watching the Rendille water their camels in the wells of the Merille sand river, I couldn’t help but think of Osa and Martin Johnson and one of their little safari disasters that occurred here. In her book Four Years in Paradise, Osa doesn’t really touch upon it. She writes about meeting a Rendille chief (they don’t really have chiefs, but never mind) who had fifteen wives and over a thousand camels. “We bought some of his camels for pack purposes and our headman had a grand day bargaining with his master’s wealth, paying forty to sixty shillings apiece.”

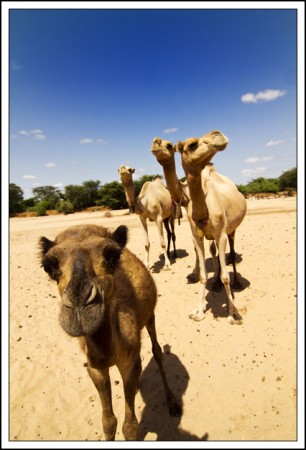

Sure, I look cute now. But wait until I blow my nose all over your camera. Photo and video by David Lansing.

And then we don’t hear about the camels again for the rest of the journey. But according to Pascal James Imperato, who wrote a biography of the couple, Martin made a huge mistake in purchasing the camels as his men had no idea what to do with them or how to handle them. “This led to inordinate delays as the camels bucked and threw off their loads.” Following his and Blayney Percival’s unsuccessful search for a shorter route to Lake Paradise through the Mathews Range, “Martin wisely traded his five camels for posho and donkeys, regrouped his seventy men, three vehicles, and mule and ox wagons, and on March 24 (1924) headed north toward the Kaisut Desert.”

That’s why we don’t hear about the camels again from Osa—Martin had gotten rid of the nasty critters. Watching the little Rendille herders work with their camel herds, I could see why it could be a disaster to use them for pack animals if you’d never worked with them before.

Even for the Rendille, for whom the camels are their lifeblood, these suckers were cantankerous, spitting when annoyed, ignoring repeated swats on the rump with sharpened sticks, wandering off when they just didn’t feel like doing what the herder wanted them to do. The fact of the matter is, camels look kind of cute from a distance, but you really don’t went to get too close to them—as I found out when one decided to blow his nose on me just as I was snapping his portrait. Snotty bugger.

Recent Comments