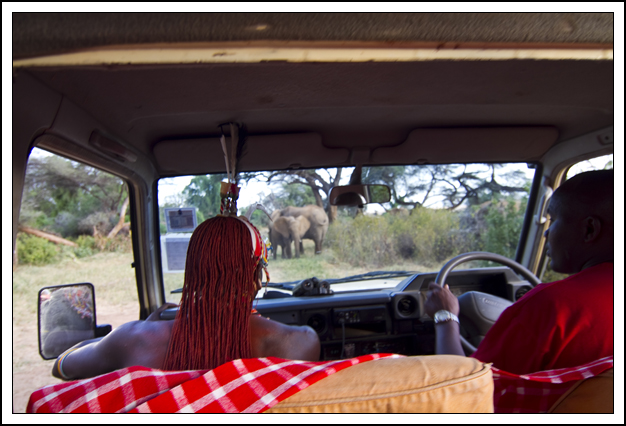

Late this afternoon Pete and I went out with Simeon and a Samburu moran looking for game. It didn’t take us long. Five minutes from camp we came across an open woodland where at least two families of elephants were feeding. Even though there were lots of totos in this group, the elephants weren’t the least bothered by our presence. We sat in our open-air vehicle while the cows with their calves passed within feet of us. Simeon was able to identify most of the elephants.

“They all have different characteristics,” he said. “Some are playful, some are cranky, some are mischievous.”

There is Baby Breeze, he told us. “Do you know Baby Breeze?”

We didn’t know Baby Breeze. Evidently Baby Breeze is almost as famous as Dumbo. Last year Iain Douglas-Hamilton and his daughter Saba were involved in a BBC documentary called The Secret Life of Elephants which shadowed several Samburu elephants and their struggle for survival. Two of the stars were Baby Breeze and his mother, Harmadon. Baby Breeze was born during the bad drought of 2009 and the question in viewer’s minds was, Would Baby Breeze survive? Well, he did. And now people come to Elephant Watch Camp just to see Baby Breeze and his mom, along with other members of the Winds family.

I should explain about the whole elephant family thing. Iain and his staff at Save the Elephants have named all the elephants and put them into families. So there’s Chagall and her calf Miro who are members of the Artists family, Baby Oscar Wilde who is from the Poetics, and, of course, Baby Breeze who is from the Winds family.

This all makes me a little uneasy. I can see how, if you’re studying elephants or any other animal, it is necessary to distinguish amongst them, but anthropomorphism is always a slippery slope, particularly with wild animals. First we give them names, like Chagall or Breeze, and then we give them human characteristics, like this elephant is playful but not very bright and that one is a trickster, and then we turn them into cartoon characters and they stand up on their hind legs and start singing “Hakuna Matata” like Timon, the “no worries” warthog from The Lion King (Timon, by the way, is Swahili for “absentminded or careless”). And then they’re just like people, aren’t they? Or maybe they’re better than people because they’re “simpler” or “purer.”

How do you make rational policy decisions regarding wildlife once they’ve taken on human characteristics? An old bull elephant may be raiding the shamba of a Samburu manyatta and destroying the crops that feed an extended family of 100 people, but who is going to give the order to cull Pretty Bom Bom, a notoriously bad-tempered bull elephant in Samburu?

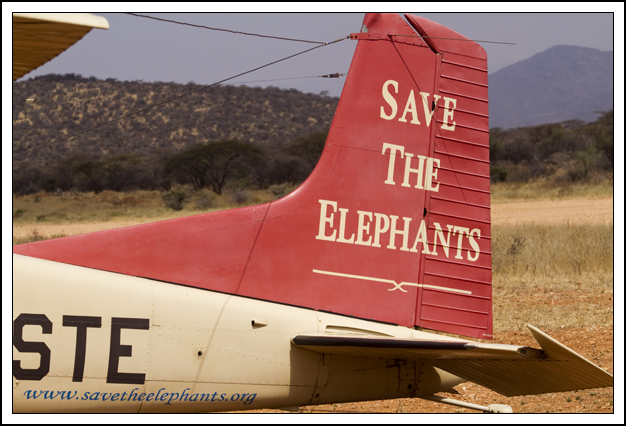

So here’s the dilemma people like Iain Douglas-Hamilton face: His organization depends on the generosity of donors, most of them Westerners and primarily from the U.S., to support his research. In order to get people to cut him a nice big check, he has to do more than just shout, “Save the elephants!” He has to make a Disneyfied documentary that gives elephants names, like Baby Breeze, and then write a heart-breaking narrative about the Winds family struggle for survival and accompany it with a moving score and the whole thing has to make you feel that if you don’t send a big check off to Save the Elephants today, Baby Breeze just might die.

Now if you do all that, and your funding depends on donors who are now invested in Baby Breeze and want regular updates on how he is doing, how do you ever make logical, scientific decisions that might call for the culling of some animals?

Here’s what Iain Douglas-Hamilton said to me: “I’m not universally opposed to hunting as a form of wildlife conservation in Kenya. I have to say that it depends. And what it depends on is whether it could be a controlled policy and with the proper profitable land use. But it could never be used with elephants because elephants are smarter than other animals.”

Are they? Or, in giving them names and families and human characteristics do we just like to imagine that they are? I mean, have you ever heard of the Save the African Wild Dog organization? Well they’re out there. And African wild dogs are much more endangered than elephants. They’re just not as cute. They have a reputation for being ruthless and vicious and pests. So they don’t get the financial support that Save the Elephants does. But are they really less worthy of our attention? Are elephants “smarter” than African wild dogs and should that really determine which species gets saved and which one doesn’t? Anybody up for Save the Hyenas?

Recent Comments