“The twisted tree trunks and the dangling moss give the forest that enchanted look reminiscent of illustrations in a tale from the Brothers Grimm. There is often a haunting silence in this forest, broken only by the tolling of a far-off dove, and a calm made uneasy by the knowledge that lion, buffalo, and leopard lurk in the hidden ravines.

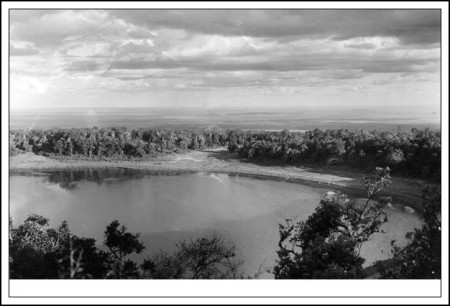

“Deep forest smells drift on the early morning breeze and thousands of butterflies hover above the lake and around the numerous pools. The somber shade of the forest is broken at one of the mountain’s highest summits by an extinct volcanic crater the Africans call Gof Sokorte Guda. It is in the center of this high crater that Lake Paradise nestles, surrounded by broad green meadows that stretch to the forest wall. From the crater’s rim one can see the Kaisut Desert stretching off to the south and the jagged purple and gray slopes of the Ndoto Mountains to the west. Great white puffs of clouds drift over the crater’s rim and cast broad shadows on the blue surface of the lake.”

Such was the description of Lake Paradise when Osa and Martin Johnson first came here in 1921. We came here because we wanted to know if it still existed and did it look the same as it did when they were here almost 90 years ago. The answer is yes—for the most part.

The ancient forest is still here and the twisted tree trunks are still covered in Spanish moss that does, indeed, give the place an enchanted, fairy-tale look. And the thousands of butterflies are here as well; this afternoon we stopped the Land Cruiser on the road that goes around the top of the crater and watched as a cloud of butterflies hovered over wildflowers that none of us have ever seen.

Then in the afternoon we climbed up to the crater rim that overlooks the lake and sat on what felt like the rim of the world, watching as a large herd of buffalos made their way down to the meadow.

Now here’s where things are a bit different from the way they were when the Johnsons came here in the ‘20s: the lake is all but gone.

Osa described it as “shaped like a spoon, almost a quarter of a mile wide and three-quarters of a mile long” but now it is just a very boggy meadow with a glistening of small pools in the middle where the elephants and buffalos go in the mornings and afternoons for a drink. In fact, it looks as if it there were a drain in the middle and someone had pulled the plug and all that remained were shallow little pools of water in the center.

Why is this? It’s hard to say. This area—in fact, all of Kenya—has just come out of a long drought that was so horrendous that this January the lack of rain was called a national emergency. So although the rainy seasons were good this year, perhaps the aquifer is so low the lake is not able to sustain itself.

Another possibility is bore holes. The tribes that live up here—Borana, Rendille, Gabbra—have long been nomadic pastoralists, meaning that a village of several hundred would stay in one area only as long as the grazing and water was good for their camels and cattle and goats and then move on. But that started to change when aid agencies came in and drilled bore holes for water. Sounds like a good thing, right? Dig a well so they have a year-round source of water? But the problem is that in Northern Kenya, there isn’t steady or reliable rainfall. So while in the past the tribe would move south or west or east to wherever there was water and grazing, now they just stay put. And depend on the bore holes. Which, as the aquifer lowers, need to be drilled deeper and deeper. Until there is no water and the wells are abandoned. And, of course, with hundreds of bore holes drilled all around the Marsabit area, the hydraulic pressure that would have kept water in Lake Paradise even in a dry season, is no longer there.

So the lake is drained dry. And even in good rain years, like 2010, remains dry. Another example of NGOs doing good deeds that end up having disastrous consequences because nobody considers the long term ramifications.

Tags: Lake Paradise

-

finished the story in one particular? boy, the center of the lake looks particularly boggy. i wonder if one could walk across it?

-

I keep coming back to your photo, which is of an ancient volcano. The older photo may have been taken by a large-format camera. Your camera may be of smaller format, and at a wide zoom may have introduced some barrel distortion. If it did not, that volcano floor center seems higher than in the older photo… Any recent tremors?

Comments are now closed.

6 comments