I’d always sort of imagined whisky distilleries as being bustling places with lots of red-faced Scots scurrying about doing this and that. But actually it doesn’t take many people to make whisky. A handful, really. And if you visit a Scottish distillery this time of year, you’re likely to find it mostly deserted. Or closed (many traditionally do maintenance in August or just shutter the doors completely).

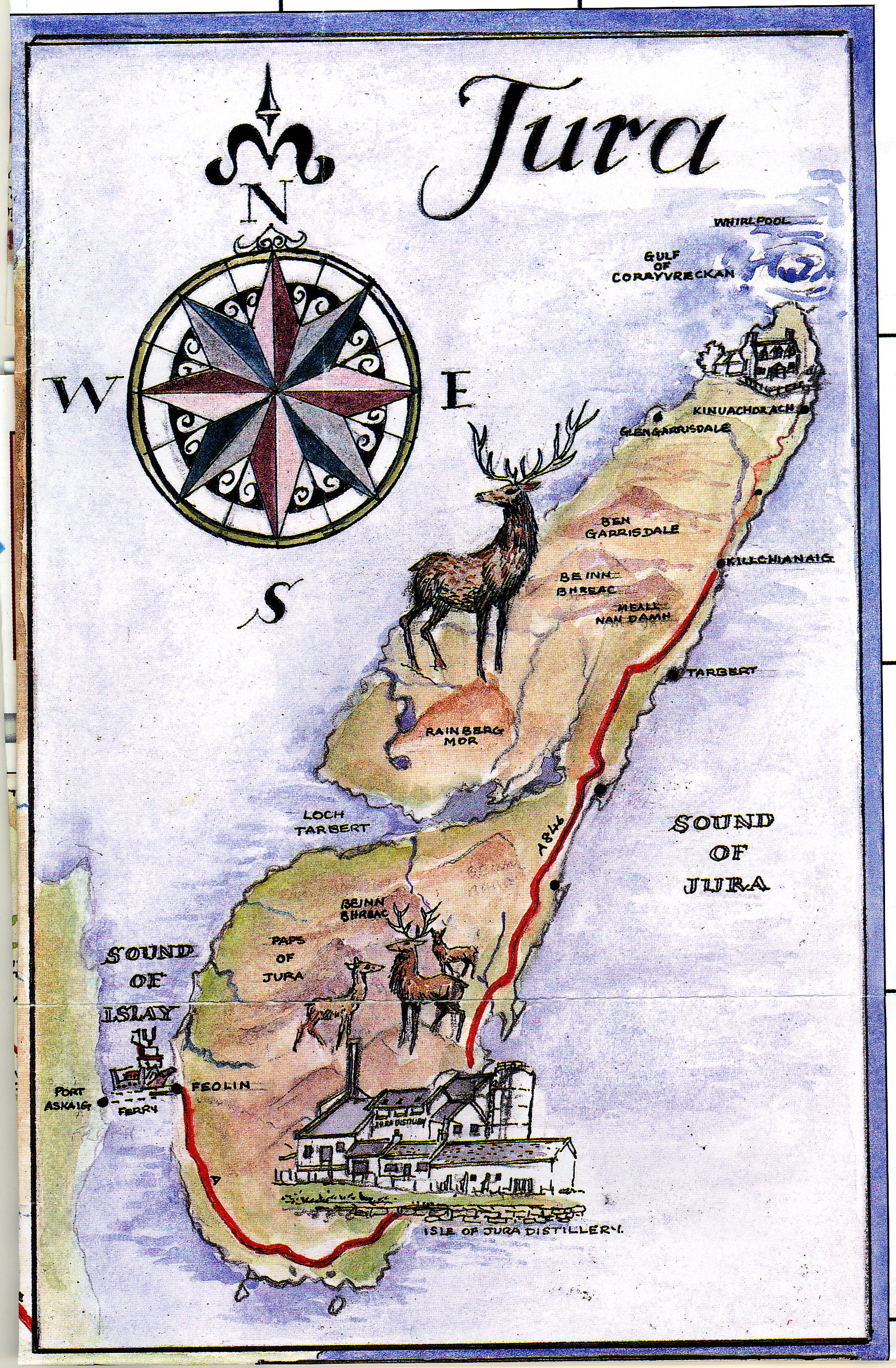

Photo by David Lansing.

That was pretty much the situation at Bruichladdich (brook-laddie) when Charles and I showed up this morning around 10. The gates were open but we didn’t see a single soul on the premises. Eventually we ended up in the little shop that serves as a visitor center of sorts where a middle-aged woman reading a book seemed surprised to see us.

She said the only one around at the moment, other than herself, was one of the four partners, Andrew Gray, and he’d be happy to show us around if she could only find him. So while she’s out looking for Andrew, let me tell you a little bit about this unique distillery.

First of all, Bruichladdich is a bit of a whisky phoenix. Like a lot of Scottish distilleries, Bruichladdich had its ups and downs over the years (there used to be 25 distilleries on Islay; now there are 7).

Bruichladdich itself closed for a spell in the late ‘80s before being acquired by four separate corporate owners (including Jim Beam and Fortune Brands) from 1992 to 1994. But nobody really seemed to know what to do with the company and in 1994, the distillery was pretty much closed down for good, devastating the town on the west coast of Islay.

Then four friends—Mark Reynier, Simon Coughlin, Jim McEwan, and Andrew Gray—got together and purchased the closed distillery in December 2000. After months of restoration work, Bruichladdich officially reopened on May 29, 2001 before a crowd of 3,400 ecstatic islanders (a good chunk of the population). They now have 47 employees, all from Islay, and in just a few short years have won a number of prestigious awards, including Distillery of the Year three times. Kind of a nice story, don’t you think, particularly in an age when most of the Scottish distilleries are now owned by huge international conglomerates like Diageo (in fact, the company, whose philosophy is to be “fiercely independent, non-comformist, and innovative—the enfant terrible of the industry” refuses to join the Scotch Whisky Association because, they say, “We feel our independent status and freedom of expression would be compromised” by the council whose board includes three members from Pernod and three from Diageo).

Anyway, Andrew was eventually rounded up and for the next couple of hours, we sat around with him loosely discussing Islay whiskies in general and Bruichladdich in particular.

“The characteristic of the western islands is they get a lot of rain—as much as 160 inches a year. So the ground is very wet and there are lots of bogs. Peat is a primary heating source and the whisky coming from Islay have a real smoky, peat flavor that people either love or hate—there’s no middle ground with this whisky. Plus all the distilleries are situated by the sea. The casks are all maturing in a briny, salty atmosphere. There’s often salt caked on the outside of the casks. It seasons the casks and gives them a different flavor.”

That said, Andrew said that Bruichladdich, which contains about 5 parts per million of peat, isn’t nearly as smoky tasting as whiskies like Lagavulin and Laphroaig which contain between 35 and 45 parts per million.

Then Andrew immediately contradicted himself by pouring us a dram of a new Islay single malt they’re distilling called Octomore. Now I love Laphroaig but I have to say I could hardly swallow Octomore. Andrew chuckled at my reaction. “That’ll put hair on your chest, eh,” he said. To be sure. The whisky, which Andrew calls “for serious peat freaks,” has a mind-boggling 131 parts of peat per million.

With the subtlety of a sledgehammer, it’s definitely not for everyone—including me. But I love the idea that these “fiercely independent, non-conformist” whisky makers, who brought this distillery back from extinction, have the balls to make it. It’s certainly not something you can imagine Pernod or Diageo ever doing.

Recent Comments