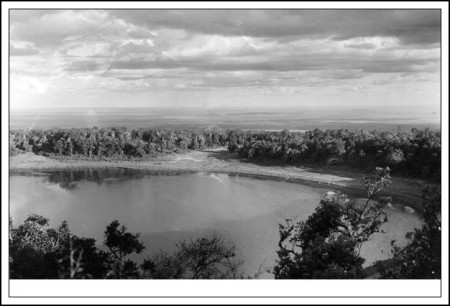

I awoke this morning just before dawn to the sound of Karani pouring a pail of hot water from a sooty aluminum pot into the canvas washbasin set just outside my tent. A low cloud cover hovered over the caldera and a cool breeze rustled the gray-green leaves of the trees above us. As I ran a steamy wash cloth over my dusty head, I watched massive dark shapes—elephants—come out of the forest on the far side of the bog and tromp slowly through the mud, wondering how they manage to not get suck.

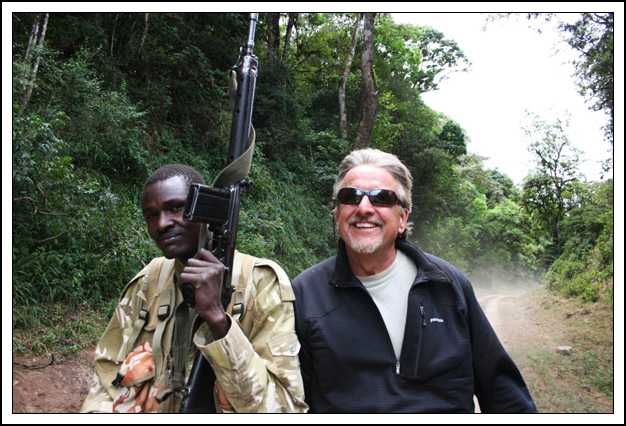

Calvin was standing by the smoldering camp fire, talking to an askari holding an automatic weapon. An askari is a soldier or someone in charge of security, depending on how you want to look at it, and three of them, working for the Kenya Wildlife Service, have been assigned to guard us during our stay at Lake Paradise. They have a campi up in the forest atop the escarpment and we are unaware of their presence except when we are exploring in the forest and they suddenly appear out of nowhere. Like the forest elephants, they are silent when they move through the woods and, also like the elephants, they can be deadly. Calvin says the KWS doesn’t hire just anybody to be askaris. “These guys know what they’re doing. Undoubtedly they have been in many, many firefights.”

Firefights with who? With the shifta who roam this part of Lost Kenya. So the question becomes, are these armed guards here to protect us from the animals or from the shifta? No one says so but you have to think it’s to protect us from the Somali bandits.

While it’s nice to know that you have someone sleeping in the forest who is here just to protect you (there are no other people here at Lake Paradise and, from the looks of things, I’d say there hasn’t been for quite some time), it’s also a little disconcerting. Yesterday afternoon, we decided to take the barely visible track that goes along the rim of the crater (actually, it’s only a partial road; half the time it just disappears into thick bushes and you have to bull your way through) and when we reached the spot on the cliffs directly above our camp, an askari came out of the shadows, his weapon slung over his shoulder, stopped us, and climbed atop our Land Cruiser. He said something to Calvin in Swahili and then we drove on, us looking for elephants and the askari looking for…well, whatever or whoever it was he was looking for. Did I feel better about having an armed soldier riding on the roof of our vehicle? Not really. But that’s the way it is in Paradise these days—good and evil must travel together.

Recent Comments