Dia de Muertos (Day of the Dead) isn’t just one day in San Miguel, it is many. It begins today, on what we call Halloween, around noon, although the town has been slowly gearing up for things for the past week. Around the churches and at the arts and crafts market next to the mercado, vendors have set up little booths where they sell an incredible selection of alfenique, the special sugar skulls and candies used to lure the dead back home.

A lot of the candies look like toys: baby blocks, bunnies, dolls, ducks, Disneyesque dogs. These are meant to entice home the angelitos, the little angels, the children who have died and are celebrated tomorrow on dia de todos santos—All Saints’ Day. It’s also a tradition here to buy a calaveritas de azúcar—a sugar skull—with the names inscribed on the forehead. So you’ll see little boxes of sugar skulls with pink or blue lettering for José or Maria or Juan. It’s not unusual to see a mother walking through the market with a child who will spot a calavera with his or her name on it and beg their mother to buy it for them.

The market is also filled with vendors selling pan de muerto, the traditional bread of the dead, made with egg yolks and orange water, topped with dough in the shape of human bones, as well as mole and sweet tamales. In fact, here in San Miguel, the indigenous people, the Otomi, who live out in the countryside, make a special sweet tamale, colored green or lavender or pink, just for the angelitos.

I like to walk the streets in the early evening during the dias de muertos celebrations hoping to catch a glimpse of a neighbor’s ofrenda, the special altars set up in a niche in the house or in the courtyard dedicated to dead relatives. Some are simple affairs: a small table covered in clean white linen with a cross in the middle or a statue of the Virgin, decorated with cempazuchitl, the yellow or orange marigolds that lead the dead back, a photo or two of the departed, and their favorite foods and drinks—tequila, beer, tamales, chiles, mole—and, if they were smokers, a pack of cigarettes.

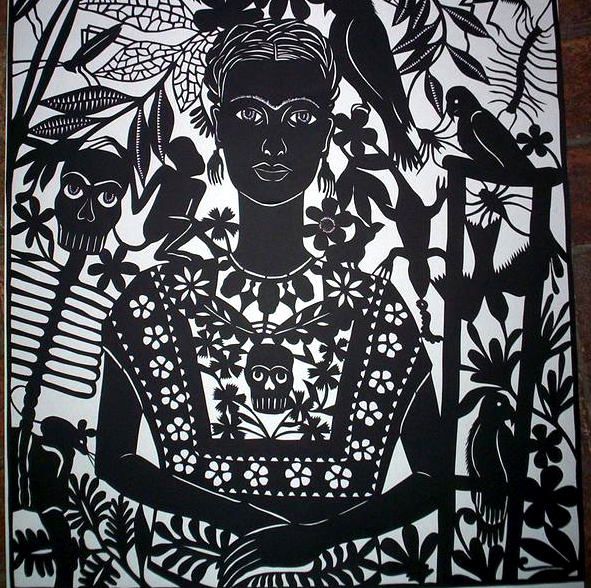

Some are much more elaborate, featuring hundreds of alfenique in the shape of little corn, bananas, oranges, chiles, and gourds, as well as tableaus of the saints and crosses, decorated with both Christian and Aztec symbols, that are works of art in and of themselves.

So I go to the market and buy a few sugar skulls, some copal resin incense, a Cuban cigar, and a bottle of Presidente brandy and set up a little ofrenda on the table just inside the door in my house. I decorate it with fishing lures, a toy figurine of a rhinoceros, some good Spanish cheese, and a faded copy of a book I always travel with, The Sun Also Rises. My dia de muertos offering to Papa.

Recent Comments