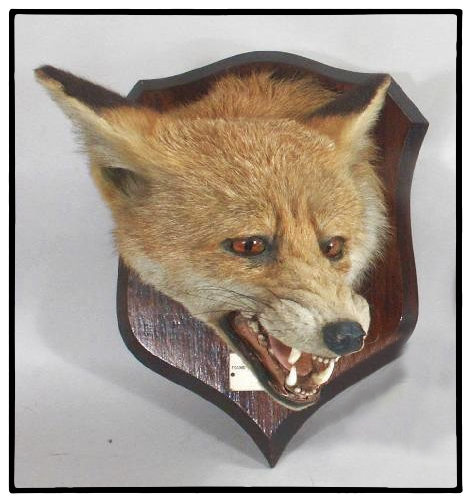

As our guide, John O’Driscoll, took us around Strokestown, filling us in a bit on the Mahon family’s eccentricities, I couldn’t help but think of a castle I visited on the Isle of Rùm, off the west coast of Scotland, a few years ago. Kinloch Castle was built by a very strange man named Sir George Bullough who liked dead animals, Victorian pornography, and playing with dynamite (not necessarily in that order).

At least one of the Strokestown Mahons also seemed to have an affinity for both dead animals and pornography, if not dynamite. The dead animals were everywhere: birds, forest creatures, exotic animals from other continents. Little of the pornography was on display, and what you could see was actually pretty tasteful, although no doubt shocking back in Victorian times. But the odd connection between the dead animals and pornography at Kinloch Castle and Strokestown House made me wonder if there wasn’t some sort of weird UK secret society back in the day where the lords of the manors got together and shot a fox or two, then retired for cocktails while sharing each other’s pornographic photos. How else to explain it?

Recent Comments