Our expedition consists of nine peeps (a “peep” being river lingo for people like myself who go river rafting on organized adventures), a six-person Wrecking Crew (the support staff), two yellow inflatable neoprene boats with oaring frames in which the peeps travel, a pontoon boat with an outboard motor on the back, which Arlo calls the “J-rig,” carrying most of the crew as well as food supplies, and Arlo’s ducky—an inflatable kayak tied atop the pontoon boat.

There is, as you can see, a unique vocabulary that comes with river rafting. For instance, the large metallic kitchen boxes that hold much of our food are called Sarah Jane’s World in recognition that nobody ever gets into them except our cook, Sarah Jane. The rope secured around the perimeter of the inflatables, used to grab on to when we run rough water, is called the chickie line (the Wrecking Crew never, ever uses the chickie line; only the peeps) and the plastic wash buckets used to do dishes and the like are called chickie pails (because they look like chicken feed buckets).

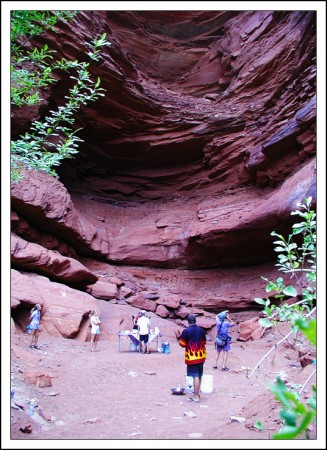

We seldom see the J-Rig which acts as a sort of advance team for our little party. When, for instance, we pulled onto a rocky sandbar this afternoon and made our way through a dense thicket of tamarisk to a hollowed-out indentation in the limestone cliffs known as Tex’s Grotto, our lunch—sliced ham, turkey, cheese, tomato, lettuce and two different types of bread, along with fresh fruit, chips, cold drinks, and chocolate chip cookies for dessert—was neatly arranged on a cloth-covered portable aluminum table, thanks to Sarah Jane and the other crew members who had arrived here an hour earlier.

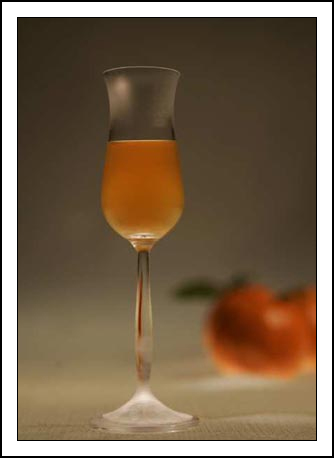

As I walked up to the table for lunch, Arlo handed me a chilled Budweiser and then reached into his dusty daypack for his well-worn copy of a journal from the second exploration of the Colorado written by Frederick Dellenbaugh, Powell’s assistant topographer. He read of Dellenbaugh’s description of his own first meal on the river, a modest helping of fatty, sandy bacon. “But how good it was! And the grease poured on bread! At the railway I had scorned it, and now, at the first noon camp, I was ready to pronounce it one of the greatest delicacies I had ever tasted.”

Stashing the book in his backpack, Arlo says, “River running makes everything taste good.” He’s right. Never before have I contemplated the complex flavors of a chocolate chip cookie washed down with a cold beer.

Recent Comments