I still don’t have a clue as to who the Lebanese are. Are they mad, fun-loving, neurotic, image-conscious, corrupt, kind, proud or paranoid?

Yes.

Yesterday I went to the Virgin bookstore next door to the grand Mohammed al-Amin mosque (I know, right?) and asked a clerk there if he could recommend a book that might help me understand the character of the Lebanese people. He suggested two books: The first is titled Spirit of the Phoenix: Beirut and the Story of Lebanon and looks to be one of those serious treatises often written by former BBC journalists (which it is), and the second, Life is Like That: Your guide to the Lebanese is an illustrated tongue-in-cheek exploration of various Lebanese stereotypes compiled by the editor of the Lebanon Daily Star, Peter Grimsditch, (who claims to be a devotee of raw liver and arak for breakfast) and Michael Karam, a Lebanese expat who returned to Lebanon in 1992.

I should probably have started with the more serious exploration of the Lebanese but the truth is I find the comic exploration of what it means to be Lebanese much more entertaining.

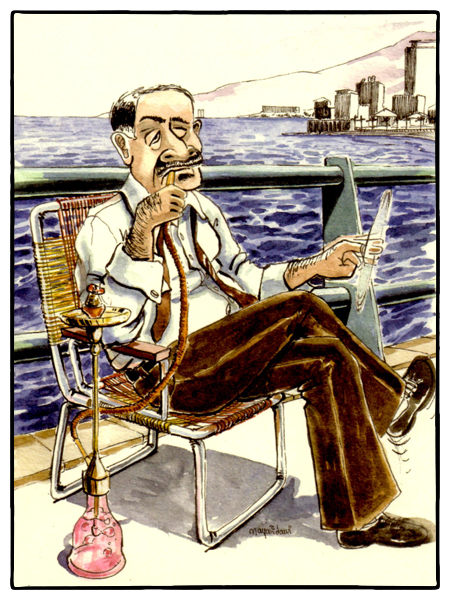

Here is authors Peter Grimsditch and Michael Karam’s take on “The Arguileh Smoker”:

“Arguileh smoker is a serious sort of chap. He is a government employee, and therefore by nature a man who knows what he wants in life; and that is a good honest smoke. While soccer fans may argue the merits of Ansar over Nijmeh, he devotes serious time to the seemingly endless debate over what is the best tobacco: m’aasal or ajami? In fact, he despises devotees of the former. They are nothing more than faddists, lightweight smokers, swept up by the recent trend for aragueel. The tourists have made the arguileh as common as a hamburger. And as for those plastic caps and the easy-to-light charcoal, well that just proves his point. He learned to smoke at the age of six when his grandfather, the village abaday or hard man, gave him his first puff. That time he nearly fainted but by the time he was ten he had the lungs of a man of 50. These days, he and his fellow smokers often take their families for roadside picnics where they unpack their luxury arguileh travel kits made by Mansour of Aleppo.

“On these occasions they find true contentment as their wives cook mishweh. But if the truth were told, there are few times in lives that are not arguileh time. He has been known, spontaneously, to spark up on the corniche on a Sunday afternoon and even during working hours at the ministry, where his job, which involves pointing people in the direction of the photocopier, is ideally suited to his favorite pastime.”

Recent Comments