When we got back to the camp it was only 10:30 but I was so tired I felt like we’d just climbed Mt. Kenya. Everybody had thick black mud covering their hiking boots and clothes and we were all dirty and sweaty and anxious for a shower. I asked Kurani to heat some water and when it was ready, he and Keith poured it into a bucket that was tied with a rope to a tree limb. There was a pipe coming out of the bottom of the bucket and a lever attached to that so when you pulled it, water reached a small showerhead. The water was hot—scalding hot—and I thought about getting out of the shower and wrapping a towel around me and going back into camp and asking Kurani to add some cool water to the bucket but it seemed more trouble than it was worth. Instead, I just wet a wash cloth with the scalding water and let it cool off a bit before soaping myself down. This wasn’t the best method for cleaning up but I managed.

Everyone took a shower and then, exhausted, we all disappeared into our tents and collapsed on our cots to take a mid-morning nap. I can’t remember the last time I took a nap before noon but this one was truly necessary. When I woke up about an hour later, I was still aching all over. As soon as I swung my legs off the cot, I started cramping up. First in my thighs and then in my calves and then all over. Even the muscles in the soles of my feet and the short muscles around my ankles started cramping. It was so bad I couldn’t walk. I stood up and tottered out of the tent, afraid I might pass out. It was like I was hooked up to an electrical current and my whole lower body was being shocked and going into spasms. There was nothing to be done but try to walk so I just kept moving, like some sort of Frankenstein creature, through the camp and down towards the meadow. One by one the spasms went away leaving me with legs that felt bruised as if from a car crash.

When I went back to the tent to put some clothes on, I saw that all of our muddy clothes and boots had been washed while we napped. My green khakis and socks were spread out on the fly of my tent and my Italian hiking boots, which I’d assumed had been irretrievably damaged from the mud and ooze, were wet but spotlessly cleaned. Everyone else’s clothes and shoes were drying out in the sun as well.

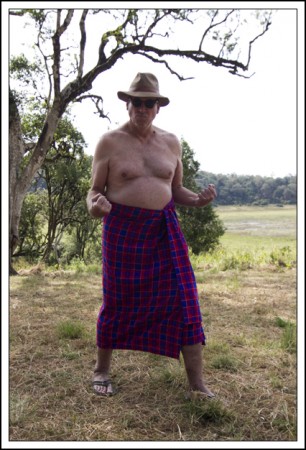

We sat in the warm sun, half-dressed or, in my case, with just a shuka around my waist, talking over the morning adventure with the buffalos and our trek through the mud, everyone reminding me over and over that I’d been advised not to continue moving into the deep part of the meadow and wondering why I’d kept going and why I hadn’t indicated to anybody why I was stuck.

“Lansing, what were you going to do?” Hardy said. “Just stand there in the mud until the elephants came back?”

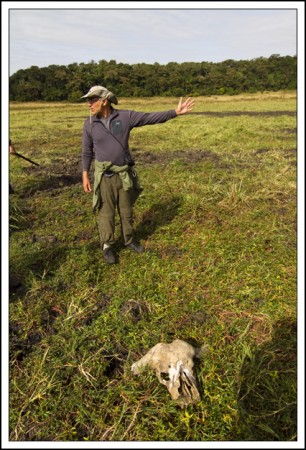

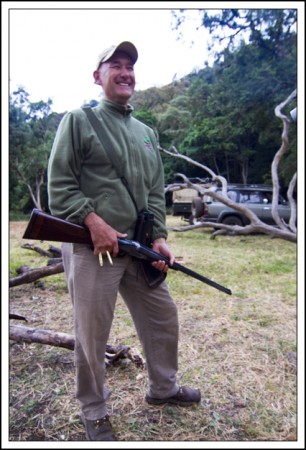

It was a good question and one I didn’t really have an answer to. I had gone against everyone’s advice and gotten myself stuck in the mud, like a mastodon in the La Brea tar pits, and once that had happened, I’d decided against calling for help. Maybe it was pride and maybe it was just stupidity but for whatever reason, I got myself stuck and I felt responsible for getting myself out. Except that wasn’t going to happen. Ever. I was in so deep that if Calvin hadn’t decided to come out and rescue me, I’d still be there. And the animals would have come down and finished me off and then my bleached bones would have stayed down in the meadow. Just like those of the buffalo Hardy had found.

Recent Comments