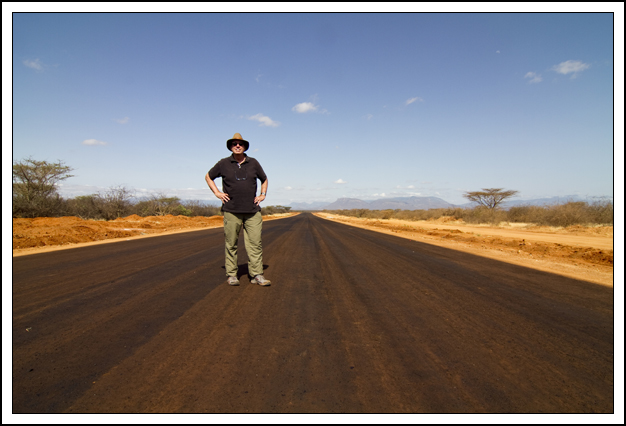

The road we are on is variously called the Cape to Cairo Road, the Great North Road of Africa, or—my favorite—the Highway through Lost Kenya. Mostly it’s just the standard African corrugated dirt track that shakes you like a martini but every once in awhile we’ve hit a stretch of pristine blacktop where we can drive for ten or fifteen minutes without coming across another vehicle traveling in any direction before it suddenly ends just as quickly as it began and we’re back on the corrugated road again.

These short stretches of tarmac (which are officially closed but we haven’t seen any construction going on so Calvin figures what the heck and runs on them when he can) are part of a multi-million dollar road being built by a Chinese firm called China Wu Yi that eventually will stretch from Mombasa, on the coast, to Nairobi and then all the way to Addis Ababa, Ethiopia.

The most important section is the one we’ve been hurtling over from Isiolo to the Ethiopian border, about 530 km. of road that has never been paved. So why would the Chinese be interested in building a road from Ethiopia to the Kenya coast?

Because they’ve been carrying out oil exploration up here in Northern Kenya and in Ethiopia and are expected to start drilling sometime next year. So, if they find oil or natural gas (and let’s be honest—of course they’ve found it! Why else would they spend $65 million to build a tarmac through a stretch of Kenya that is so isolated from the rest of the country that when people in the north head for Nairobi they say they are “Going to Kenya” because they just don’t feel a part of the country?) they’ll need a way to transport it or will need to build a pipeline. In either case, they’ll need a road.

The trouble is that the Kenya government has always had a hard time controlling the Northern Frontier District. Kenya’s Lost Land has for over a hundred years been troubled by shiftas—Somali bandits that steal cattle, poach elephants, hijack vehicles, and, every once in awhile, murder intruders. Just this April a Chinese engineer working on the construction of the road was shot and killed near Merille, where we watched the Rendille wedding ceremony, by shiftas who, supposedly, weren’t happy that the day laborers building the highway were mostly Chinese. Or maybe they just didn’t like their noodles. In any case, the project was shut down for awhile and eventually many of the Chinese were sent home and now Kenyans are on the job. Which may explain why we haven’t seen any construction going on during our drive. Fortunately, we also haven’t seen any shiftas.

Here’s a 30-sec. video of our photographer, Pete McBride, explaining where we’re going on the Chinese highway to Lost Kenya.

Recent Comments