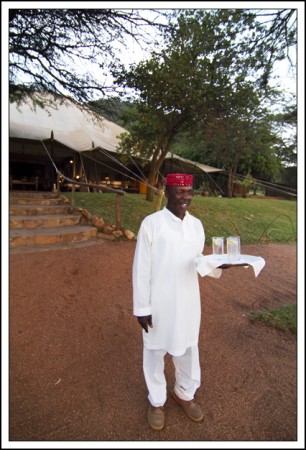

Just in front of the main mess tent at Cottar’s 1920s Safari Camp is a fire pit and around the fire pit are a dozen or so canvas camp chairs. If you happen to be sitting in one of the chairs about half an hour or so before the sun sets, as Hardy, Fletch, and I were, William, a very handsome man who never wears anything but white except for his colorful prayer cap, which he seems to change several times a day, will come down and take your drink order.

When Ernest Hemingway was here in the 1930s, hunting with famed guide Philip Percival (who was called “Pop” in the Green Hills of Africa and, most think, was Wilson, the great white hunter with “cold blue eyes” in Hem’s classic short story “The Short Happy Life of Francis Macomber”) they drank beer and whiskey. Mostly whiskey.

In the Green Hills of Africa, Hemingway, after a difficult but successful hunt of a great kudu (whose head is still hanging over the dining table in Hemingway’s old home in Havana, Cuba), trudges back to camp in the dark, exhausted, and “In the firelight I sat on a petrol box with my back against a tree and Kamau brought the whiskey flask and poured some in a cup and I added water from the canteen and sat drinking and looking in the fire, not thinking, in complete happiness, feeling the whiskey warm me and smooth me as you straighten the wrinkled sheet in a bed…”

So naturally enough, we all brought fine bottles of whisky along for this trip. Hardy ordered a whisky from William and Fletch, who doesn’t drink hard alcohol very often, asked for a Tusker, and I was going to ask for a whisky as well but the evening was warm and my throat was parched so I asked for a gin and tonic.

William nodded and had started back to the dining tent when Hardy said, “You know what? I think I’ll have a gin and tonic as well. That sounds rather good.” And then Fletch also changed his order to a G&T.

William brought the drinks and I don’t think anything has ever tasted so wonderful to me in my life. I drank half of it straight down, relishing the bitterness of the tonic and the pungent juniper berry taste of the British gin, and had to tell myself to slow down, afraid I’d finish it before William even had a chance to make it back to the bar set up in the back of the dining tent where a linen table cloth was being smoothed by another waiter over a long table in preparation for our dinner.

Calvin had said earlier in the day that it might rain. The sun was holding itself up in a sliver of sky between the dark silhouetted hills and several long, heavy rain clouds. Far away on the horizon, towards Tanzania, you could see a rain shower falling somewhere over the Rift Valley.

We talked about the elephants we’d seen and wondered if the old cow in charge of the herd’s safety really would have come after us if she’d seen Hardy walking around in the bush. It seemed unlikely. Dangerous animals, like elephants, don’t like to feel hemmed in when you’re between where they’re coming from and where they’re going, like a water hole. But although the herd was coming our direction from up the donga, it seemed likely that they’d been in some water down there and were now just moving up onto higher ground to feed in the tall grass. There was no particular reason, as far as we knew, for them to come our way, so the old cow just changed course and went around us.

While we were talking and watching the sky go from gold to burnt orange to dark purple, a very tall, bald Masai, wearing a traditional tartan cloak and heavy hiking boots with gray socks pulled up halfway to his knees, brought an armload of kindling wood over to the fire pit. He put several small twigs in a cross-hatch fashion and, on his knees, twirled a fire-stick between his palms until the twigs started to smoke. He blew on this and a flame shot up and slowly he added more twigs and kindling until he had a proper fire going just as the sun disappeared behind the dark hills.

Calvin came up and asked what we were drinking. He ordered a gin and tonic from William, who seemed to suddenly appear out of nowhere from the shadows, and I asked for another and then Hardy said, “Better just bring us four more, William.”

The drinks came, the second one tasting even better than the first, and we sat around the fire asking Calvin questions about the camp and his great-grandfather, Charles, who Calvin said probably came to Kenya with his family in 1915 because “he had some problems back home and needed to make a quick escape. Family legend has it that Charles Cottar was a bit of a scoundrel and probably in trouble with the law.”

We finished our second round of drinks as the night came on and the fire roared and it was almost nine before Calvin suggested that we’d better head up to the dining tent for dinner where the other guests of the camp had already finished eating and were now having coffee. Still, no one immediately got up to leave. The evening was too fine to rush.

Tags: Masai Mara

-

the G&Ts.. i can taste them from here. what kind of english gin? beefeaters? and way to hold up the dining efforts boys, winning over the kitchen and wait staff already i see.

Comments are now closed.

3 comments