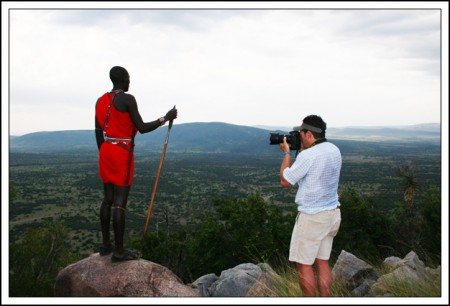

We flew west into the Mara, following the migration route of tens of thousands of wildebeest and zebra below us as they crossed the Sand, or Longaianiet, River following the border between Kenya and Tanzania. The Masai word siringet, from which we get Serengeti, means “vast place” and why they called it that becomes apparent when you fly low over it. In front of us was an endless horizon of tawny yellow grass, sometimes so tall you could see the wind flowing through it like waves, interrupted only by the dark green vegetation along the Sand or the distinctive island kopjes, little rock islands poking out of the yellow grass that, like coral reefs on an ocean floor, become their own little mini eco-systems supporting birds, lizards, hyraxes, and maybe a resident leopard or a pride of lions.

Sandwiched as we were between heaven and earth, what you become aware of, besides the vast numbers of wildlife beneath you, is the way all the colors of the Serengeti compliment each other: ocher-colored earth; grass going from khaki to umber to chartreuse; the deep green of trees and bushes along the riverbanks. All set off by a very pale blue sky that just seems to stretch out in front of you endlessly.

Martha Gellhorn, Hemingway’s third wife, in writing about the Serengeti, talks about the vastness of this sky, how it seems to have “no boundaries, no end,” and how this is almost more than she can handle. “The machinery that keeps me going is not geared to cope with infinity and eternity as so clearly displayed in that sky. After sunset, the Africans jam into their round huts and close everything up to keep out the night; if I understood nothing else about them, I understood that.”

Flying over the same terrain, I knew exactly what she was talking about.

The Sand River eventually merges with the Mara River at the southeastern corner of the Mara Triangle and here we turned north. Below us were what looked like a dozen or so big black rocks in the middle of the mud-colored water—hippos. This river is the banquet hall for crocodiles and lions and other predators for it’s where the lemming-like wildebeest cross in order to get to the lush grasslands in the Mara Triangle. Thousands and thousands of the animals will come to the steep banks of the Mara, stop, nervously look around, grunt in frustration, and wait for a leader—anyone, anyone?—to finally dive into the stream and swim across to the other side. Once that single wildebeest makes his move, the entire herd follows—first slowly, then in a nervous panic, like fans at a sold-out soccer game, stampeding from behind so that animals are trampled to death or break their legs running down the cliff or simply drown in the pandemonium. Meanwhile, the crocs and the lions wait, no doubt with smirks on their face, for an easy meal.

From here we flew over the Mau Forest whose rivers, like the Sand, are the water source for the Mara (as the trees go—and they are being free-cut at an alarming rate, as we could see flying over them—so goes the plains) and up to Lake Nakuru, flying low over the western edge as we watched an ungodly number of bright pink flamingos rise up out of the salty soda lake, circle, and land back where they started.

Then up over the verdant Aberdare Forest to the western edge of Mt. Kenya, cloaked in a dark cloud, to the airport at Nanyuki where Calvin and the boys were sitting on the tarmac in their Land Cruisers waiting for us.

Recent Comments