A letter from Ireland

Walking along the seawall in Cobh, past a stand selling sea-salt ice cream from Dingle (why ice cream from Dingle?) where a small fella no more than three takes a lick, his chin pointing to the sky, and rolls the melting brown scoop off his cone and—plop!—on to the sidewalk. Seagulls scurry over, flapping their wings and fighting over the drippy mess as the small fella looks at his mom and balls.

It’s no matter, she says, grabbing at his free hand and dragging him away from the disaster. We’ll get you another. Stop your bawlin’ now. But the child, inconsolable, cries on. As do the gulls.

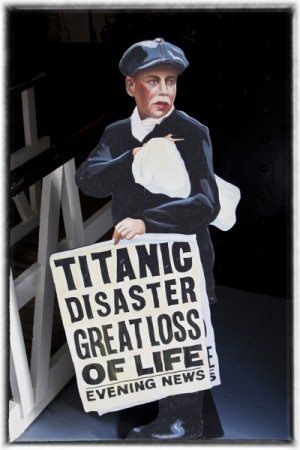

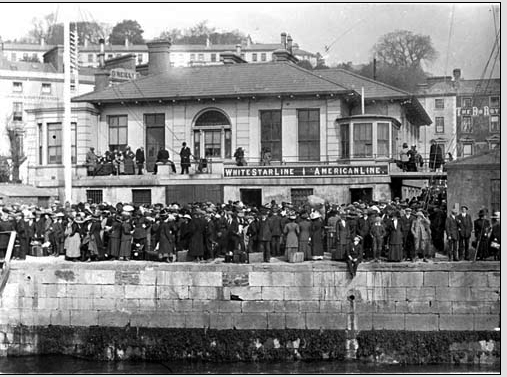

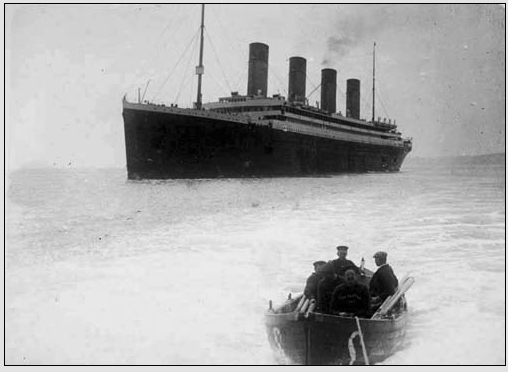

Just behind the spot of the ice cream disaster is a boarded up building with a real estate sign hanging over the front door. Across a broad gate with two porthole windows, bronze letters, a foot high, say TITANIC. It was from this very building that the last of the ill-fated liner’s passengers boarded on the 11th of April, 1912. Inside the sealed building were the three first-class passengers and seven second-class passengers, sipping tea and eating biscuits while waiting for the tender that would ferry them out to the waiting liner. In front of the large gate with the porthole windows would have been the other 113 steerage passengers, waiting to board a separate tender (couldn’t mix the first-class passengers with the third-class passengers, even for a 15 minute ferry in a tender, now could you?).

The ice cream slowly melts. The brown ooze of the chocolate cone spreads like a stain on the worn concrete. And it was here—right here—that those passengers last stood on land. Ever.

Pity something useful isn’t done with this building. For a few years it was a restaurant. Odd story. Seems there was an Irish man on the dole who, after getting his support check, promptly went off and bought a lottery ticket. Won over a million pounds (this was before the euro). Good for him. Not two days later he gets a notice from social services saying his name has been removed from the roles. Don’t come calling again. Well, at the time, the social services office was in this very building which were once the offices for the White Star Line. So what does our man do but go out and buy the building. And double the rent of the social services. How do you like them crackers? Social services moves out, of course. So our man spends a good portion of his winnings to turn the building into a restaurant called Titanic, going so far as to replicate the look of one of the ship’s dining rooms. Cost a bloody fortune. And then the Celtic Tiger dies. Economy tanks. Restaurant goes bankrupt. And our man is now out of money. Probably back on the dole.

So there she sits. The former offices of the White Star Line, the very spot where the last passengers boarded the Titanic for her maiden voyage. Now just a boarded up, bankrupt restaurant. As sad looking as a child’s ice cream cone melting on the sidewalk.

Recent Comments