Well, this is a bit embarrassing. When we landed at the Samburu airstrip there was nobody there to pick us up so the pilot checked his phone and saw that he had a text message from Tropic Air saying we were to land at the other Samburu airstrip. The only problem was that they’d sent the text message about 20 minutes after we took off from Marsabit so he hadn’t gotten it. No biggie. We just piled back in the little Cessna and rolled down the bumpy dirt runway, got in the air for all of about five minutes, and then landed again at the correct field.

On the flight from Marsabit Hardy talked the pilot into hanging out at Elephant Watch Camp for a couple of hours instead of flying straight on to Nairobi, so all four of us as well as the pilot jumped in to the safari vehicle that was waiting for us and being driven by a couple of Samburu, one with braided hair colored with ochre mud. Along the way we had to stop for a few minutes as a cow and her calf were pulling limbs off some trees while standing in the road and obviously didn’t want to be interrupted. Eventually they moved on and so did we.

The camp itself, located on the sand banks of the Ewaso Nyiro River, is quite beautiful in a rustic sort of way, being built out of wood scavenged from fallen trees and mud walls and thatched roofs. It’s hard to believe that pretty much the entire camp was washed away in floods earlier this year and has been completely rebuilt by Oria and her staff.

Iain and Oria weren’t here when we arrived but we were told they’d be here soon and we’d all have lunch together, and perhaps while we waited we’d like to have tea. We sat in a sort of outdoor living room area down by the river. There were woven mats on the sandy ground and a comfortable couch and tables made from driftwood beneath lacy acacia trees filled with vervet monkeys. The black-faced vervet is certainly more genial than the baboons we’d been used to at Lake Paradise, although like the baboon he can be rather dastardly and you have to watch out they don’t pee on you or worse.

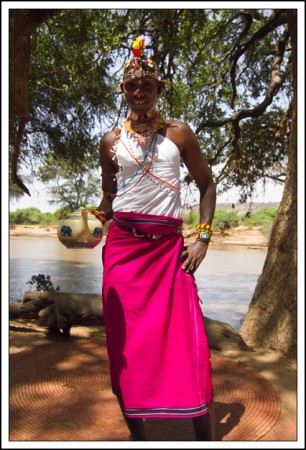

We ordered tea which was brought out to us by a Samburu moran dressed up in a flamingo pink shuka and tons of beaded jewelry. He poured us a cup and we sat there in a languid state listening to the starlings and the monkeys in the trees and the gentle sound of the river floating by. We kept hoping that Oria and Iain would show up so we could have lunch and Hardy and Fletch could meet them before they had to get back to the airstrip, but it wasn’t to be. So we gathered ourselves up and sat on the couch for a final group shot and then Hardy and Fletch and the pilot got back in the safari rig and we all said our goodbyes and even though Pete and I will be staying on here at the Elephant Watch Camp, it felt like our expedition to Lake Paradise and our journey was truly over. And not wanting it to end just yet, Pete and I decided to go back to the airstrip with Hardy and Fletch and watch them fly away. Which, sadly, we did.

Recent Comments