I’m still trying to understand the various ways in which wildlife is protected in Kenya. It’s very confusing, even to those who live here. There are Kenya game parks and Kenya game reserves, and then there are wildlife ranches and wildlife conservancies. Masai Mara is a national game reserve; Mt. Kenya is a national park; Cottar’s 1920s Safari Camp is in the Esoit Maasai Ranch while Sarara Camp is in the Namunyak Conservancy. But they all manage and preserve wildlife. Got all that?

I’m probably going to make a mess of this, but let me try and muddle my way through it. The main difference between a national park in Kenya and a national reserve is this: In a park, human habitation is excluded. To quote from the National Park Trustee’s report of 1951, five years after Kenya established their first national park, Nairobi National Park: a national reserve denotes a preservation area “where the reasonable needs of the human inhabitants living within the area must take preference.”

So, in a reserve, it’s people over animals.

The Masai Mara became a national reserve in 1974. The reason it was not made a park is because there were thousands of Maasai living here with tens of thousands of their goats and cattle. There was no way in hell you could displace them. And there never will be. In fact, each year it gets a little (or a lot) worse in the Mara because pressure from the Maasai and their livestock continues to squeeze out the animals. Everyone is competing for the same resources: land, grazing grass, and water.

Okay, now what about ranches and conservancies? Let me try and explain it by telling this story: After WWI, Britain tried to increase the number of British settlers in Kenya by setting up a “Soldier Settler” entitlement program that gave land to Brits who built a residence and lived on their property in Kenya. One of those old soldiers was named Alec Douglas and he established a cattle ranch north of Mt. Kenya in an area called Lewa Downs. After he died, his daughter, Delia, inherited the property and with her husband, David Craig, ran the farm for 26 years before handing it over to their eldest son, Ian (who we are supposedly having lunch with today).

So Ian Craig, just like his father, ran a cattle ranch. Until Kenya passed a law in the late 70s outlawing hunting (which turned out to be a disastrous move—but more on that later) and the country’s wildlife population was decimated by poachers. When I say decimated, I’m not kidding. After the hunting ban, the number of black rhinos in Kenya dropped from an estimated 20,000 to fewer than 300 in about five years.

In an effort to save what few rhinos were left, in 1983 the Craigs set aside 5,000 acres of their cattle ranch as a rhino sanctuary. Now here’s the tricky part: all the wildlife living on their ranch, including the rhinos, belonged to the Kenyan government. But the land, which was private, was the Craigs. So far so good?

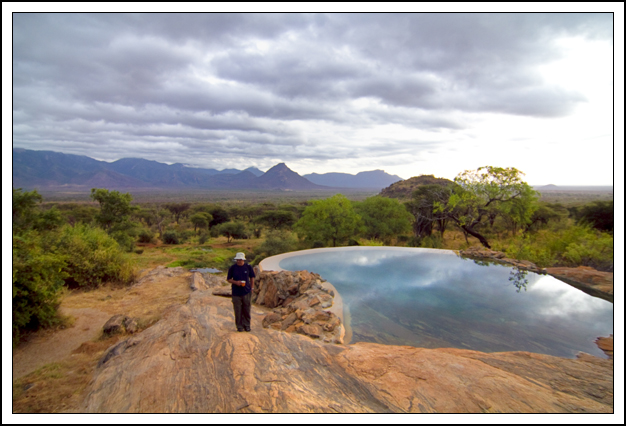

This project was so successful that in 1995, the whole of the Craigs’ old Lewa Downs ranch, as well as the state owned Ngare Ndare Forest Reserve, was enclosed with 100 miles of electric fence, both to keep animals in and poachers out, and officially became the non-profit Lewa Wildlife Conservancy, which is now home to more than 300 people and encompasses over 62,000 acres where some 70 different mammals, including 65 black rhinos, and over 400 species of birds live.

So while the impetus for converting Lewa Downs from a cattle ranch into a conservancy was a private initiative to save black rhinos, what it has developed into is a community conservation area that gives jobs to the local tribes, protects their livestock, and funds schools, health clinics, and the like.

This is all very complicated but also very important because the bottom line is that the real heavy lifting in wildlife conservation in Kenya is really being done not in the National Parks but in the community conservancies.

It’s all about Abraham Maslow’s “hierarchy of needs” pyramid theory: Before people can care about animals or even other people, first they must have the basics—food, water, shelter, health, and security. The rest will follow. That’s what the community conservancies (as opposed to the national parks and reserves) are doing. And both Lewa and Sarara, as well as Cottar’s 1920s Safari Camp, are shining lights in this regard.

What does this mean to you? It means that should you ever want to visit Kenya to see wildlife, it is massively important where you decide to stay: In a lodge where the money is going to end up back in the pockets of some multi-national conglomerate and the minions of the Kenyan government or in a camp owned and operated by a community conservancy where the cash goes back into their pockets so they have more of a reason to preserve wildlife rather than shoot it?

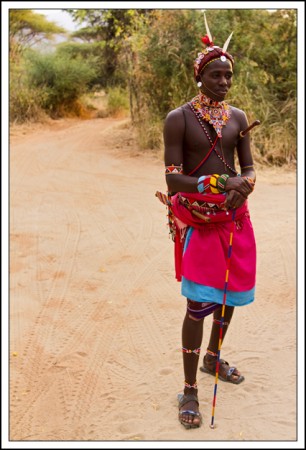

Consider this: the Maasai in the Mara receive nothing from your visit (and, in fact, even the game wardens there have a hard time getting paid) while Sarara is owned by some 7,000 Samburu and the camp generates over $150,000 annually to those who live there. So they have a reason not to shoot the elephants. Because they are a valuable resource.

Now where would you rather stay?

Recent Comments