“In the early hours of the morning we came to the sand river of Merille, lined with dom-palm and mimosa trees.

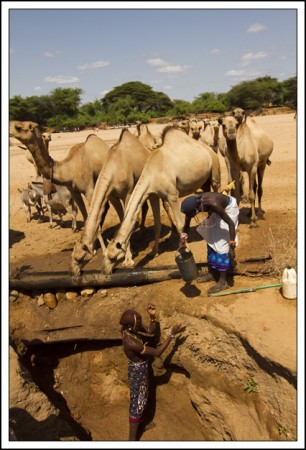

“We had no sooner arrived and replenished our water, than I saw a huge cloud of dust on the horizon, which would be natives bringing their flocks to water. We waited, and sure enough, the camels began to arrive. Then came goats and sheep and humpbacked cattle, until the place was thick with dust.

“Martin sent out boys to reassure the natives, who proved to be Rendille, and when they settled down to their watering Martin set up his cameras, but the dust made it difficult to take pictures. The Rendille natives continued to arrive with their herds until there were thousands of groaning camels. Except for carrying water, these camels are generally accumulated only for wealth and display. Such trade as the Rendille carry on is always in exchange for camels, and the trade is mostly for wives, which they also accumulate. A wife fetches as many camels as her beauty or her working ability seem to warrant, the rate varying from one to three camels per wife.”

–Osa Johnson, Four Years in Paradise

In the early hours of the morning we also came to the sand river of Merille, and there, just as they’d been when Osa and Martin Johnson passed this way in 1924, were Rendille herders watering great herds of camel, humpbacked cattle, goats, and donkeys. Almost nothing had changed.

The farther north you go in this country the drier it gets and here the herdsmen had dug wells that were considerably deeper than the singing wells of the Samburu and it took two or three Rendille to pass the bucket up from the bottom to the top.

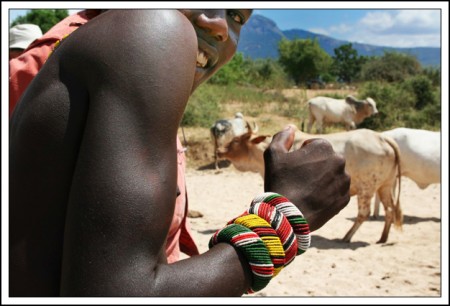

Despite the vast number of animals waiting for a drink, everything was quite orderly. A herd of maybe 50 camels would stand at a distance from the well, waiting until a young boy with a sharp stick was told to bring forward maybe eight or ten beasts and they would drink their fill as the others patiently waited their turn. Behind the camels were the herds of cattle and goats and donkeys, all separated and in specific locations in regards to the wells, and around all the animals were the young boys who maintained order with their herds and beyond them, farther out in the circle, clumps of Rendille women with their babies on their hips or at their breasts (the women are not allowed to talk or fraternize with the men). The women were ornately dressed with the same colorful nkelas wrapped around their waists and lots of beaded necklaces and bracelets.

Despite the vast number of animals waiting for a drink, everything was quite orderly. A herd of maybe 50 camels would stand at a distance from the well, waiting until a young boy with a sharp stick was told to bring forward maybe eight or ten beasts and they would drink their fill as the others patiently waited their turn. Behind the camels were the herds of cattle and goats and donkeys, all separated and in specific locations in regards to the wells, and around all the animals were the young boys who maintained order with their herds and beyond them, farther out in the circle, clumps of Rendille women with their babies on their hips or at their breasts (the women are not allowed to talk or fraternize with the men). The women were ornately dressed with the same colorful nkelas wrapped around their waists and lots of beaded necklaces and bracelets.

In fact, the Rendille and Samburu are very similar, both semi-nomadic herders who probably came originally from Somalia. The Rendille language is very similar to that of the Samburu as are many of their customs (like marriages, arranged by parents, that are usually between an older man and a young girl and in which livestock is used for the dowry). The Rendille, however, prefer camels for their herds rather than cattle, primarily because their lands, mostly in the Kaisut Desert, are so dry and the camel is better suited to this environment.

The Rendille have been resistant to change (they believe they came to live in the desert because it is their promised land and pray to a god called Wakh and thank him for leading them to the desert “because your people cannot climb mountains or cross seas”), but it was interesting to note that while the women and men wore the traditional costumes, most of the young children were dressed in the hand-me-down t-shirts and shorts that come bundled in bales from Western aid societies and are meant to be distributed free but usually end up with some dukawallah who sells them cheaply in little shops or markets. Perhaps this is a sign of things to come for the Rendille.

Recent Comments