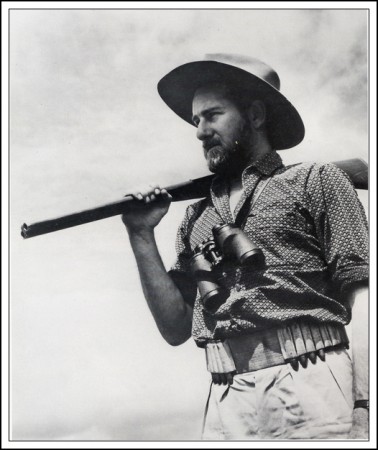

We’re not just stalking cheetahs during the day and drinking whisky around the campfire at night. That’s a pleasant part of our stay here at Cottar’s 1920s Safari Camp, but the more important task is planning and preparing for our long expedition, which starts tomorrow, to Lake Paradise about 850 kilometers north of here, not far from the Ethiopian border.

One doesn’t just get in one’s vehicle and drive up to Lake Paradise. For one thing it is situated high up in the Northern Frontier District, or NFD, which is a rather lawless territory plagued by Somali bandits called shifta (those Somali bad boys aren’t just out in the Indian Ocean being pirates). For another thing, about 250 kilometers or so of the drive will be over corrugated dirt roads. Or worse.

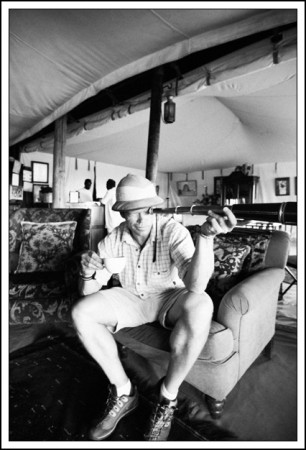

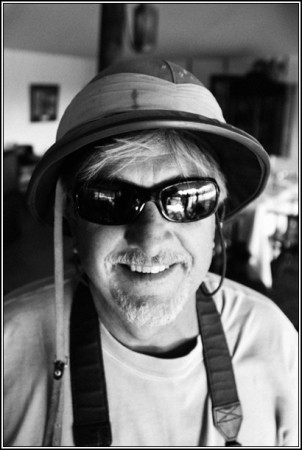

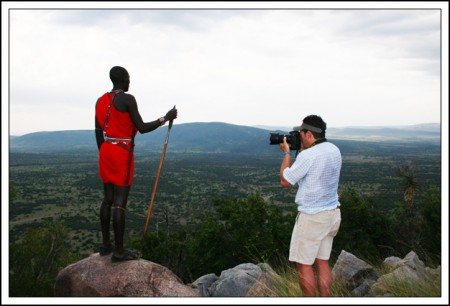

And there is little in the way of supplies along the way and absolutely nothing once we get there. We will have to carry all our own food, water, gasoline, and beer, of course. The way the plan is at the moment, we will have two four-wheel drive vehicles plus a trailer loaded with our camping equipment and food as well as a support staff that will include Calvin as expedition leader; Keith, a guide and driver; Julian, our cook; Eddie, our mechanic (Calvin likes to say about Eddie that he is such an incredible mechanic he could rebuild an entire engine in the bush); and Karani for security and to help out. Plus the four of us: Pete McBride, a photographer from National Geographic Traveler; Hardy McLain, a London producer; Chris Fletcher, my agent; and me.

Because we’re covering a lot of ground, we’re going to travel via a mixture of flying and driving. Calvin and his crew headed out early this morning for Nairobi to stock up on everything we’ll need for the expedition and to load the vehicles before heading north. Meanwhile, tomorrow Pete, Hardy, Fletch and I will fly with Hamish, our pilot, in the Caravan, to Nanyuki, on the western slopes of Mt. Kenya, where we’ll hook up with the rest of the group and begin the long drive to the Sarara Camp in the Mathews Range, an area I’ve heard is one of the most beautiful (and seldom visited) in Kenya.

We’ll spend a fair amount of time at Sarara in an area known for great herds of elephants as well as reticulated giraffes, which are slightly smaller but, I think, more elegant looking than the Masai giraffe around here. We’re also expecting to find Grevy’s zebra here. The Grevy’s differs from the common zebra we’ve been seeing in that they have white bellies and round ears.

From there we’ll begin the worst section of the trip, a hideous drive across the lunar-like landscape of the Kaisut Desert in search of Lake Paradise which, according to a Lieutenant-Colonel J.H. Patterson over a hundred years ago was called Angara Sabuk (Great Water) by the local Samburu pastoralists who described the lake as “glistening like a sheet of burnished gold in the brilliant sunshine.”

I am anxious, as are others in our expedition, to discover if the lake is still there. We plan to find out.

Recent Comments