Calvin and I don’t know each other well enough yet to exchange secrets. We’ve shared a few meals and we’ve sat around the fire at his camp in the Mara drinking whisky and chatting but I wouldn’t really say we’ve had that big breakthrough conversation yet where you say to yourself, “Aha…so now we’re going to start speaking the truth.”

What he knows is that I’m a writer who is here on assignment to do a story for National Geographic Traveler about Osa and Martin Johnson and a mysterious lake they discovered that sits atop an extinct volcano in one of the most rugged and inhospitable sections of Kenya. He also knows that I asked him to lead this expedition because it was his great uncle, Bud Cottar, who originally led the Johnsons to Lake Paradise back in the ‘20s.

But this is where things get a little sticky, where story and reality get mingled, where what I think I know about Osa and Martin Johnson and their journey to Lake Paradise might be a downright fraud at worst and simply apocryphal at best. Calvin keeps hinting that I don’t really know the true story. But he hasn’t told me what that is. I think he’s worried I can’t handle the true story.

Osa watches NYC mayor Fiorello LaGuardia sign a giant mock-up of I Married Adventure in 1940 (NYT Pictures).

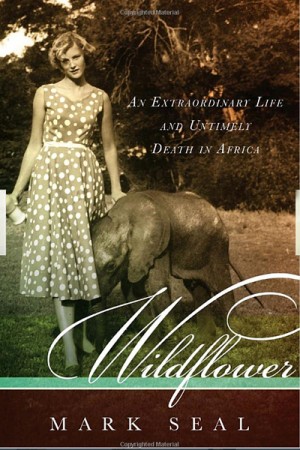

Here’s what I know: On May 17, 1940, Osa Johnson’s book I Married Adventure, with its distinctive zebra-striped cover, was published to great critical and commercial success. Its selection as a June Book-of-the-Month Club choice helped make it the number one national best-seller in nonfiction for 1940. Within the first eight months of publication, 288,000 copies were sold, which was a ton considering that the country had not yet recovered from the Great Depression. Eventually 500,000 copies were sold within the first year of publication.

I own one of those copies. I got it as a gift just after Christmas last year. And it was Osa’s description of the Johnson’s discovery of Lake Paradise that set me on the path that, eight months later, has me sitting in a crowded Land Cruiser with Calvin Cottar, bumping and grinding our way over horribly potted roads towards the Mathews Range in Kenya’s Northern Frontier District. In her best-seller, Osa Martin describes a visit from one of Kenya’s most famous and well-respected game hunters, Blaney Percival, who discreetly told them about a “crater lake which is on no map ever made of this country.”

She writes: “Martin stared at him. “You mean there’s a lake around here nobody knows about?”

“Nobody, and you may be certain I’ve kept my ears open.”

“But you’d think some of the natives would have run across it,” I said.

“It’s probable; but if they have, they’ve guarded the secret just as carefully as I have and probably for the same reason.”

“A lake,” Martin said with mounting excitement. “Why, animals must go there by the thousands!”

Blaney nodded. “Yes, and probably from hundreds of miles in every direction—a sort of sanctuary, undisturbed by the white man and his gun. That’s why I’m telling you about it, Martin. I’d like to see you go there some day with your camera and come back with a record of what animals are really like in their natural, undisturbed state.”

Martin was beside himself with excitement. “Well, man alive,” he shouted, “let’s go! Why waste time on the Athi River? Why waste time on anything?”

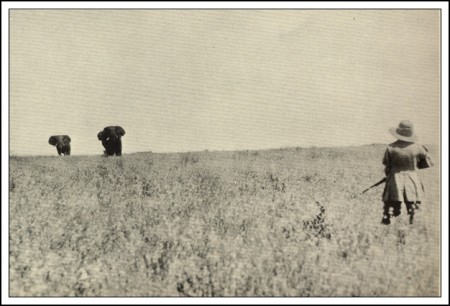

And so they went on an incredibly difficult safari to the north, crossing the fields of volcanic lava and the Kaisut Desert, having no idea exactly where this lake was supposed to be or if it was even really there until, weeks later, after days and days of marching “over some of the roughest country I’ve ever crossed…completely without warning, we were at the edge of a high cliff overlooking one of the loveliest lakes I have ever seen.

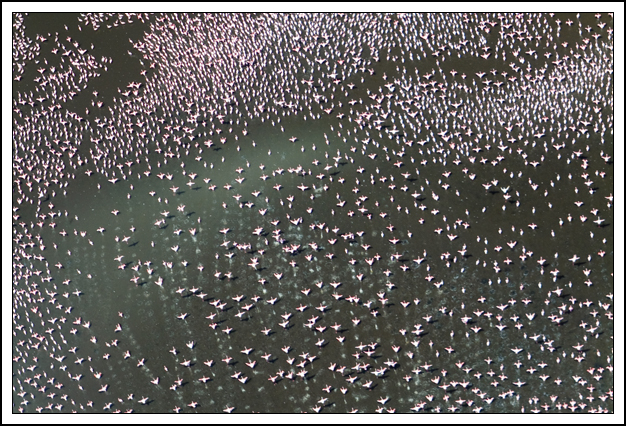

“The lake was shaped like a spoon, almost a quarter of a mile wide and three-quarters of a mile long, and it sloped up into steep, wooded banks two hundred feet high. A tangle of water-vines and lilies—great African lilies—grew in the shallows at the water’s edge. Wild ducks, cranes and egrets, circled and dipped. Animals, more than we could count, stood quietly knee-deep in the water and drank.

“It’s Paradise, Martin!” I said.

He nodded.

That was how Lake Paradise was given its name.”

Lovely story. Except little of it is true. I know the truth. I think. But I haven’t told Calvin that yet. As far as he knows, I’m just this American writer come to Kenya to recreate Osa and Martin Johnson’s expedition to Lake Paradise and repeat the various stories, true or not, I read about eight months ago in a book ghost-written by a New York journalist (and not by Osa Johnson—that’s one of the truths) 70 years ago. But before I tell Calvin what I know, I want him to tell me the stories he’s heard about that expedition. Handed down through his family from his great uncle who was with Martin and Osa Johnson. And then, together, we’ll try and find the truth between the two versions. I have a feeling that everything about this journey is going to be complicated. Which I’m rather looking forward to.

Recent Comments