It’s 304 steps up a staircase flanked by nagas to reach the Thoughtful Buddha at the top of Wat Doi Suthep. Photos by David Lansing.

After feeding the monks, Ketsara suggests we should continue up the forested mountain road to Wat Doi Suthep, one of the most revered Buddhist shrines in Northern Thailand. Frankly, I’m starting to feel a little templed-out. But Ketsara, saying she has something to show me, insists.

It rains on the winding drive up. We pass by trekkers and bicyclists and small waterfalls. Everything seems cool and quiet here, particularly compared to the temples in Bangkok. There is a little village with shuttered souvenir shops below the wat. And then a long sweeping staircase, flanked by nagas, that could have been inspiration for Led Zeppelin’s “Stairway to Heaven.”

“Where does that go?” I ask Ketsara.

“To wat,” she says. “Let’s go.”

I can’t believe she’s making me do this. We stop after the first hundred steps so I can catch my breath, then continue on, up, up, in to the forest, the air getting cooler, thiner. Another painful hundred steps, and then a hundred more. By the time we reach the 304th step, I can barely breathe. Ketsara hasn’t even broken a sweat. She looks at me serenely and smiles.

“Parami number five,” she says.

“Which is?”

“Effort. Now you will appreciate wat more.”

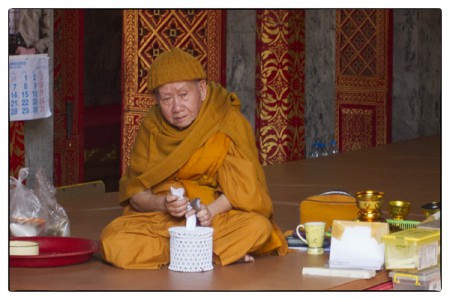

Ketsara leads me to a building where an old monk, wearing a heavy saffron shawl and a saffron knit cap to ward off the cold, sits on a platform before several gold Buddha images. Without saying anything, she kneels before him. She motions for me to kneel beside her. The monk chants and uses a baton to bless us. She drops some coins in the alms pot at his feet.

Ketsara leads me to a building where an old monk, wearing a heavy saffron shawl and a saffron knit cap to ward off the cold, sits on a platform before several gold Buddha images. Without saying anything, she kneels before him. She motions for me to kneel beside her. The monk chants and uses a baton to bless us. She drops some coins in the alms pot at his feet.

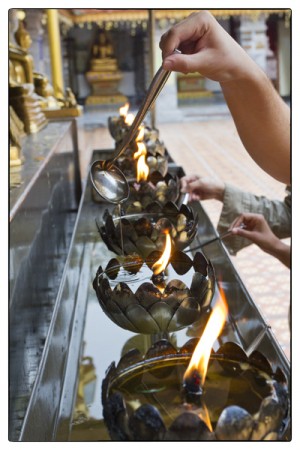

It is raining lightly. We walk carefully in our bare feet to the back of the main chedi, a striking gold-plated Lanna structure, to a trough lined by all the different Thai Buddhas where oil lamps, in the shape of lotus blossoms, burn. Ketsara takes a ladle and slowly pours oil from the trough on top of the lotus lamps. The flame jumps.

“Parami number four,” she says. “Wisdom.”

Without saying anything, she looks at me and then looks at the small gold Buddha in front of the lotus lamp she has just lit. I follow her gaze. It is the Thoughtful Buddha. Pang Rumpeung. My Buddha.

I take the ladle from Ketsara and drizzle oil over the flame which leaps and dances. Ketsara says, “Now make offering.” I take all the money out of my pocket and drop it into the alms pot in front of the Thoughtful Buddha. Ketsara smiles.

As we are taking the 304 steps back down from the wat on the mountain top, I ask Ketsara if all that was for her or for me.

She thinks about this for a moment. “We will see,” she says.

Recent Comments