As you’re walking around Istanbul’s Grand Bazaar you start to notice that various items are sort of concentrated in certain areas. There’s a hatmaker’s street and the gold and silver lane and a souk specializing in antiques.

And then there are the shops selling the all-white outfits worn by Turkish boys at their sünnet.

A sünnet is the Muslim circumcision ritual and is generally performed when boys are between the ages of 7 and 10. It signals a boy’s transition into adulthood and so, in a way, it’s like a Jewish bar mitzvah, except at a sünnet the kid not only gets to dress up and eat a lot of good food (and get presents!), but he also gets his foreskin trimmed.

Sidar told me that this is a big ritual, particularly in the smaller villages in Turkey. “Sometimes they even do it in a restaurant and invite the whole village to come watch.”

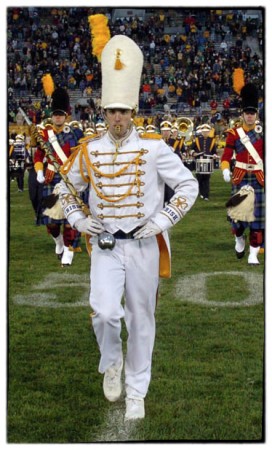

Here’s how a traditional sünnet works: A couple of weeks before the big event, invites are printed up and sent out to family, friends, and residents of the town where it’s taking place. Mom or dad goes and buys a special satin uniform, oftentimes with a hat or sash with the word Masallah (meaning “Wonderful. May God avert the evil eye,” or something like that) on the front. The day before the big event, the boys dress up in their sergeant major outfits (often the sünnet is for several boys at the same time) and parade around town in cars or, if they’re poor, in horse carts followed by musicians (this is a lot like the drum major part—see photo).

The day of the ritual, the boys put on a long, white gown. A close family friend called a kirve (sort of like a godfather) holds the boy down while the doctor or licensed practitioner performs the circumcision in front of the guests. After the circumcision, the boy is laid on a decorated bed to recover and rest while the rest of the guests tuck in to a magnificent feast. After the chow-down, the guests drop by the bed and give the kid gifts like sweets, clothing, or special gold coins, if they’re fairly well-off. Then they go off to dance, drink, and listen to music while the kid tries to keep his mind off his swelling member.

Sounds like fun, right? But, hey, at least the kid gets to keep the drum major outfit.

Recent Comments