Ireland is always a surprise. Yesterday I got to hear Dean Martin play “Danny Boy” on the church organ at St. Columb’s Cathedral in Derry. Today I had lunch with Joan Crawford. And I must say, she looks great.

Now, just as it probably surprised you to learn that Dean Martin now plays the church organ at a cathedral in Northern Ireland, I’m sure it will come as a shock to discover that Joan Crawford was, for a couple of years anyway, a flight attendant with Aer Lingus.

I told her I was sure we’d flown together.

She smiled. “I don’t think so.”

“I’m sure of it.”

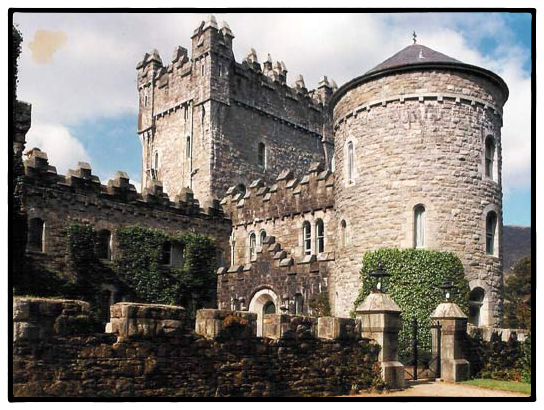

Anyway, Joan and I were having lunch at Glenveagh Castle, built in the 19th century by an Irishman, John George Adair, who made his fortune in Texas of all places.

There aren’t many who have a good word to say about Adair who was known for his hard drinking and fiery Irish temper. A story Joan Crawford told me was that one day Adair went hunting on land around the castle that he’d rented to tenants, which violated his rental agreements. The locals objected and Adair got pissed off. A year later, he evicted 47 families. More than 150 screaming children and their parents were ordered off the property, most with no idea where to go.

So, not a good man.

But here’s the postscript: He died in 1885 and the night before he was buried, a dead dog was thrown into his open grave by disgruntled locals. At Glenveagh, his wife had the face of a large rock inscribed with his name and the inscription “Brave, Just and Generous.” Which was too much even for god to swallow. Shortly thereafter, lightning in a thunderstorm broke the rock into many pieces which fell into the lake beside the castle. And two years after his death, his country mansion in Belgrove, County Laois, mysteriously burnt to the ground. It was never rebuilt and the ruins, called “The Burnt House” by the locals, are just as they were.

Recent Comments