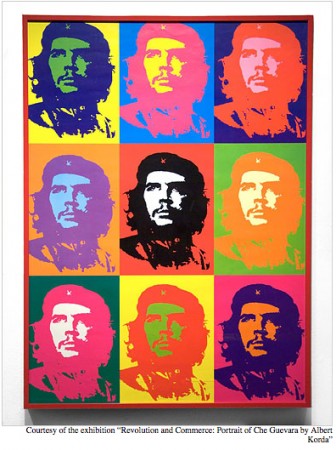

A new book by Michael Casey, “Che’s Afterlife: The Legacy of an Image,” explores how the world-famous shot of Ernesto “Che” Guevara by Albert Korda has gone from being a symbol of resistance to the capitalist system “to one of the most marketable and marketed brands around the globe…as recognizable as the Nike swoosh or McDonald’s golden arches.”

According to a recent story in the New York Times, Che’s image has been used to sell air fresheners in Peru, snowboards in Switzerland, and wine in Italy. “The supermodel Gisele Bündchen,” it claims, “pranced down a runway in a Che bikini. A men’s wear company brought out a Che action figure, complete with fatigues, a beret, a gun and a cigar. And an Australian company produced a ‘cherry Guevara’ ice cream line, describing the eating experience like this: ‘The revolutionary struggle of the cherries was squashed as they were trapped between two layers of chocolate. May their memory live on in your mouth!’”

Well, we haven’t come across any Che ice cream in Cuba, but his image truly is as ubiquitous as Starbuck’s logos in Seattle, and if you’re going to go home with a souvenir from the island, odds are it will be Che-related.

Yesterday we snaked our way up the hills outside of Viñales to a pink hotel, Los Jazmines, perched on a bluff overlooking the Valle de Viñales. The fertile valley below us, where much of Cuba’s tobacco is grown, was encircled by these dramatic rocky outcrops, called mogotes, which are ancient limestone plugs formed during the Jurassic Period.

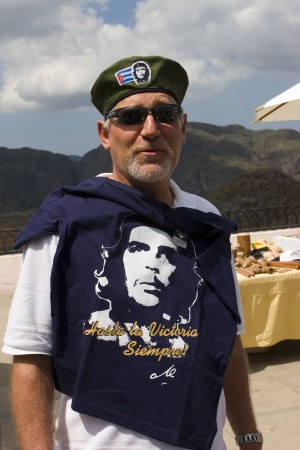

The lookout above the hotel is a spectacular setting for the dozens of little enterprises where you can get a hot dog and a mojito, a locally-produced cigar, or Che flags, t-shirts, and berets. Hardy went off in search of something to bring back to his 8-year-old son (my godson) and settled on a beret with the famous Korda image embroidered on the front.

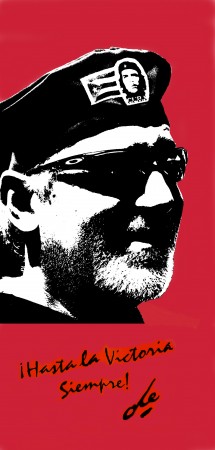

I’ve decided that my gift to my godson will be to convert the photo I took of his dad wearing the Che beret into a poster like the ones they sell everywhere in Cuba. So he can hang it on the wall above his bed. And contemplate how his father, a true capitalistic Master of the Universe, ended up on a print looking very much like one of the most infamous revolutionaries in history.

As the NY Times piece points out in regards to Che’s role in capitalistic endeavors, “Clearly, it’s not what Che Guevara had in mind when he declared that ‘the revolutionary idea should be diffused by means of appropriate media to the greatest depth possible.’ For many, Che has become a generic symbol…‘the quintessential postmodern icon’ signifying ‘anything to anyone and everything to everyone.’”

Including a little 8-year-old boy in England.

Victoria siempre!

Recent Comments