Calvin's .500 double Rigby, the same gun his grandfather and father hunted with. Photo by David Lansing.

We were talking about hunting. And how some people, including Calvin Cottar, who owns a tourist camp on the southeast border of the Masai Mara Reserve, think that the best way to save the wildlife in Kenya is to bring back trophy hunting (which was banned in 1977).

Here’s the problem in a nutshell: Wildlife has no value to the average Kenyan. Well, how can that be, you wonder, since Kenya has these wonderful wildlife parks and reserves? Because wildlife belongs to the state. And the only people who make money from ecotourism (i.e., photography safaris) are the Kenya government (and very little of this money ever makes it back to the local tribes) and the lodge operators. And as incidences of conflicts between people and wildlife increase, the animals are always going to lose.

As an example, in just one of the areas adjacent to the Masai Mara Reserve—the Koyiaki Ranch—the number of Masaai bomas or villages increased from 44 in 1950 to 368 in 2003, while the number of huts increased from 44 to 2,735. That puts a lot of pressure on wildlife that breaks down fences, damages crops, degrades water supplies, and threatens livestock and humans. So of course they’re not opposed to killing those animals. As a result, according to the Kenya Wildlife Service, “the (Masaai) country has lost a huge number of carnivores including lions, cheetahs, hyenas, and wild dogs” as well as hartebeest, impala, and other hoofed animals.

So what’s this got to do with hunting? Well, let’s take a look at elephants.

In 1977, Kenya banned elephant hunting. But that didn’t stop the demand for ivory. So poachers began butchering the herds. In less than two decades following the ban on hunting, Kenya’s elephant herd went from about 150,000 to less than 6,000.

Botswana, on the other hand, permitted big game hunting and in the same period of time, their elephant herd has quadrupled. In 1980, Zimbabwe had 40,000 elephants. That number more than doubled until around 1990 when Mister Nutso, Robert Mugabe, took over as president (the government claims they currently have 100,000 pachyderms in Zimbabwe, but the government there claims a lot of things). The point is that elephant populations have increased in countries that allow trophy hunting and decreased in Kenya where hunting isn’t allowed.

But the key to that is the germ of an idea from a ridiculously-named program called CAMPFIRE (Communal Areas Management Programmed for Indigenous Resources) under which the people living on communal lands claim the right or proprietorship to the wildlife. Thus the money made from trophy hunting goes back to the local population (and this same thing is being done in South Africa, Namibia, Mozambique, and Botswana).

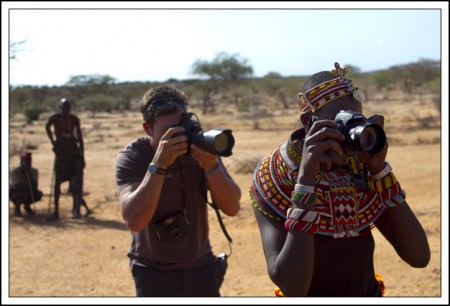

So now let’s take this general information and make it specific. As I wrote a few days ago, the hero of Lewa Wildlife Conservancy and Namunyak Conservancy, where Sarara is located, is Ian Craig who, twenty years ago, watched shifta bandits slaughter an entire family of elephants and, as a result, cut a deal with the local Samburu community and, in 1997, set up this little tented camp, Sarara, which is wholly owned by the local Samburu community. And now elephants, and other wildlife, have returned to both Lewa and Namunyak.

Which is great. Because the Samburu have discovered that they can make more money through ecotourism than they can from poaching wildlife. But, I asked Ian Craig the afternoon we had lunch together, what will the Samburu do if the price of ivory continues to skyrocket (in the last eight years, it’s gone from about $100 per kilo to $1,800 on the black market)?

“I worry about that,” he admitted. “If that happens, our model for community conservancy here would very much be at risk.” Then he went on to tell me that last year, when the price of ivory started going up again, they lost 21 elephants around Sarara. “But the community got together and sent out armed rangers and stopped it. Because they were invested in the elephants and it still made more sense for them to protect them than to kill them. But if the price (of ivory) continues to go up? I honestly don’t know what would happen. They might decide it made more sense to poach the elephants.”

Here’s the way Calvin looks at it: “It’s true that wildlife does well in places like Sarara and Lewa. But they don’t do well outside of parks and conservancies and before long there will be nothing left. The number of elephants we have seen here may very well still be present in twenty years—but we can’t sit in our lodge and look at elephants here while outside of areas like this, the wildlife is quickly being decimated. Because in the end, all we’ll be left with are urban areas ringing unnatural game ranches.

“I think the only way to save the animals, in the long run, is to give ownership of the animals to the local tribes and let them charge a fee for hunting. Then it’s to their benefit to conserve the animals. Just as is done in countries like Botswana. Otherwise, in the end, the local population will continue to allow the wildlife to decline in numbers. Think about it: Why would they not?”

Recent Comments