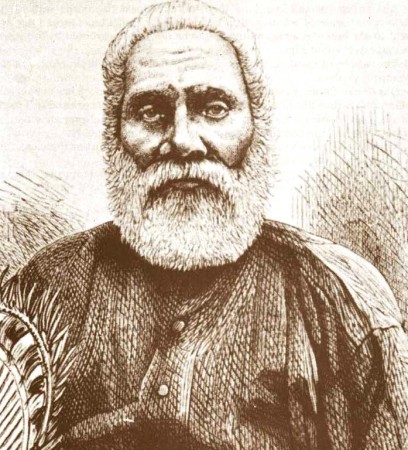

Grave of the woman who committed suicide in Levuka. Photos by David Lansing.

Sleeping has been a problem this week. Yesterday I sat in a folding chair on the wooden deck of my room, the Kei cottage, a beach towel wrapped around my shoulders, watching the sun sneak up on the meaty dark clouds out over the ocean. Around six, I pulled on some shorts and headed for the Royal Hotel dining room for breakfast. And there was Meli, sitting on the steps, wearing nothing but a pair of dirty khaki shorts and sandals. His hair was matted to one side and his eyes were sunken pools of red.

“Meli, what are you doing here so early?”

“I in a bad way, sir,” he said, slurring his words. He was obviously very drunk.

“Meli, you need to go home and clean up. You don’t want anyone seeing you like this so early in the morning.”

“Oh, I know,” he said, nodding and swaying. “I been drinkin’ all night. All night.”

“Yes, which is why you should go home now.”

“My mother, she die last night,” he said. “She make us dinner like she do and go to lie down and two hours later, she dead. That all there is to it. She dead.”

So is it the island or is it me? I’m starting to feel like I’m the worse kind of luck here.

I told Meli that I would talk to the manager of the hotel and tell him about his mother, but he should go home.

“I been drinkin’ all night,” he said again.

I helped him up. He was in no shape to find his way home. I took his arm and started walking up Beach Street, having no idea what direction his home might be, but fortunately one of his sons saw us and came to my rescue.

“I got him, sir, I got him. Sorry to trouble you.”

They disappeared up one of the side streets behind the Marist school. And I went back to the hotel and had my breakfast: toast and two fried eggs.

Afterwards, I went for a walk. Out past the fish factory and the beautiful large bure, known as the “Prince Charles House,” which was built specifically for a visit by Prince Charles in 1970 to commemorate Fiji’s independence from Great Britain. It’s the most beautiful structure in Levuka, indeed on the whole island, but it doesn’t seem to get much use. There’s nothing much past here except a few odd houses in the bush where the fishermen live. But it was a beautiful day and I had nothing I had to do so I just kept walking out along the coast road.

Which is when the funeral procession passed me by. Seven, maybe eight cars, all following a pickup truck with a coffin in the back. I stood off to the side of the road as the procession slowly passed. Which is when I noticed the family from the Ovalau Holiday Resort. The man who had given me a ride into town—the dead woman’s husband—was driving the same car I’d been in. He was by himself and looked just as crazy as when I’d been with him. Behind him was a silver mini-van. I could see the mom sitting in front and the heads of many people packed in the seats behind her. They were going to bury the woman who’d committed suicide in my room.

I turned around and started walking back into town. A fisherman passing by in a ratty old pickup truck stopped and asked if I wanted a ride. I thanked him but told him I’d rather walk. It was farther than I thought. I kept going around one bend after another, expecting to see the Pafco factory, but I didn’t. After awhile, I stopped and sat on a rock by the ocean watching two fishermen bring in their small boat and pull it up on the beach. They had a small bucket of fish. I couldn’t really tell what kind of fish it was, but I could see they weren’t very large. They finished up what they were doing, put the fish on a stringer, and started walking up a path that came by me. They stopped and showed me their catch—maybe six or seven smallish barracuda. God, I hate barracuda.

“You eat those?” I asked them.

“Oh, yes, sir. Fry ‘em up, they’re very delicious.”

They continued up the path towards a small cottage half hidden in the vines and bushes of the jungle.

I just stayed by the ocean, looking out at the water. About a hundred yards out or so, just down the coast, I could see anchored an old threadbare sloop flying a tattered British flag. It had obviously been there for awhile. I’d asked Meli about it once and he said you could see a light come on in the sloop’s cabin in the evening but no one had ever seen anyone on deck. He said he thought it was haunted.

“Fishermen stay away from that boat,” he told me.

After some time, the funeral procession came by again, this time headed back into Levuka. It seemed like the mom saw me sitting there, but I couldn’t be sure.

After they’d passed, I started walking back out into the country. Without thinking about it, I decided I wanted to walk to the cemetery, though I had no idea how far away it was. But it wasn’t far. Less than a quarter mile beyond where I’d turned back the first time.

It was an odd cemetery, built on a hill so that you had to scramble through thick brush and over boulders to get to where the graves were scattered over the hill. I had no trouble finding the grave site of the woman who had hung herself. It was the only one with fresh flowers on it. They had lined the grave with sticks and hung banners of gold ribbons on strings stretched around the sticks. The gold ribbons waved in the breeze like seaweed in the ocean. On top of the grave, made of local rock, were little pots of petunias and pansies. Very colorful. Maybe they were her favorite flowers.

Well, here she was. And here she’d be stuck for god knows how many years, wandering around the graveyard and Levuka in a sort of soulless form until she’d passed what should have been her natural age at death. And then she’d have to start all over again. From scratch. Try to get things right this time.

I felt very sorry for her and told her so. And then I walked back into town.

Recent Comments